Researchers from a range of disciplines frequently remind us of the enormous challenges that Earth will face in the coming decades. Climate change, unprecedented levels of human population, enormous amounts of resource extraction to meet the needs of that population, widespread pollution, and other characteristics of the 21st century will present humans and the other species that share our planet with conditions that, at the very least, will make life much more difficult in many places. In response to such warnings, an increasing number of studies seek solutions that will not only help us to survive, but also to maintain those parts of our world that are particularly valuable for all life. The research we describe here seeks to measure the degree to which regions of global significance for nature are also of global significance for culture, in part to provide a foundation for more effective conservation of both.

This research merges two major areas of inquiry, one examining biological diversity and the other examining linguistic-cultural diversity. One can measure biological diversity—or biodiversity—in several ways, ranging from large scales such as ecosystems to very small scales using genetics. We focused on a medium scale and considered the number of species, including endemic species (those unique to a particular locality), as a useful indicator of biodiversity. Cultural diversity, in contrast, presents a greater challenge for definition given the fundamental challenge of defining culture itself. Here we chose language as a key characteristic marking a culture, the main means of conveying the shared behavior characterizing a particular culture among its members as well as the primary mechanism for transmitting cultural behavior and knowledge from one generation to the next. We focused in particular on non-migrant indigenous languages, those linked to a particular locality and culture rather than those transplanted through colonization or some other process (such as English in the United States). Both biological diversity and linguistic diversity have been studied for decades, as has their co-occurrence. Our research seeks to measure connections between the two in regions containing particularly high levels of biodiversity and to identify opportunities (and possibly strategies) to conserve both biological and linguistic-cultural diversity in our rapidly changing world.

Linguistic Diversity in Regions of High Biological Diversity

Researchers define geographic priorities for biodiversity conservation in a variety of ways. One approach considers biodiversity hotspots, regions containing exceptionally large numbers of endemic species as well as high levels of threat to those species. Technically, hotspots contain minimally 1,500 endemic plant species and have lost at least 70% of their natural habitat (Myers et al. 2000). In plain language, these are regions that host enormous varieties of plant types unique to those regions amid widespread human impacts; if an endemic species disappears from a hotspot, it becomes extinct globally. Currently there are 36 hotspots, though when we conducted the study described here there were 35 (Mittermeier et al. 2004; Williams et al. 2011) (Figure 1). We supplemented our examination of the hotspots with five high biodiversity wilderness areas, large regions also characterized by large numbers of endemics but suffering lower human impact by having lost 30% or less of their natural habitat (Mittermeier et al. 2003). The importance of conserving these regions is enormous: nearly 70% of vascular plant species and more than 50% of vertebrate species on Earth exist only in the hotspots and high biodiversity wilderness areas. Figure 1. Biodiversity hotspots (1-Atlantic Forest; 2-California Floristic Province; 3-Cape Floristic Region; 4-Caribbean Islands; 5-Caucasus; 6-Cerrado; 7-Chilean Winter Rainfall-Valdivian Forests; 8-Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa; 9-East Melanesian Islands; 10-Eastern Afromontane; 11-Forests of East Australia; 12-Guinean Forests of West Africa; 13-Himalaya; 14-Horn of Africa; 15-Indo-Burma; 16-Irano-Anatolian; 17-Japan; 18-Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands; 19- Madrean Pine-Oak Woodlands; 20-Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany; 21-Mediterranean Basin; 22-Mesoamerica; 23-Mountains of Central Asia; 24-Mountains of Southwest China; 25-New Caledonia; 26-NewZealand; 27- Philippines; 28-Polynesia-Micronesia; 29-Southwest Australia; 30-Succulent Karoo; 31-Sundaland; 32- Tropical Andes; 33-Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena; 34-Wallacea; 35-Western Ghats and Sri Lanka) and high biodiversity wilderness areas (36-Amazonia; 37-Congo Forests; 38-Miombo-Mopane Woodlands and Savannas; 39-New Guinea; 40-North American Deserts)

Figure 1. Biodiversity hotspots (1-Atlantic Forest; 2-California Floristic Province; 3-Cape Floristic Region; 4-Caribbean Islands; 5-Caucasus; 6-Cerrado; 7-Chilean Winter Rainfall-Valdivian Forests; 8-Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa; 9-East Melanesian Islands; 10-Eastern Afromontane; 11-Forests of East Australia; 12-Guinean Forests of West Africa; 13-Himalaya; 14-Horn of Africa; 15-Indo-Burma; 16-Irano-Anatolian; 17-Japan; 18-Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands; 19- Madrean Pine-Oak Woodlands; 20-Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany; 21-Mediterranean Basin; 22-Mesoamerica; 23-Mountains of Central Asia; 24-Mountains of Southwest China; 25-New Caledonia; 26-NewZealand; 27- Philippines; 28-Polynesia-Micronesia; 29-Southwest Australia; 30-Succulent Karoo; 31-Sundaland; 32- Tropical Andes; 33-Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena; 34-Wallacea; 35-Western Ghats and Sri Lanka) and high biodiversity wilderness areas (36-Amazonia; 37-Congo Forests; 38-Miombo-Mopane Woodlands and Savannas; 39-New Guinea; 40-North American Deserts)

The definition of the regions we examined rests solely on biological indicators, so one would not necessarily expect any particularly important cultural content.

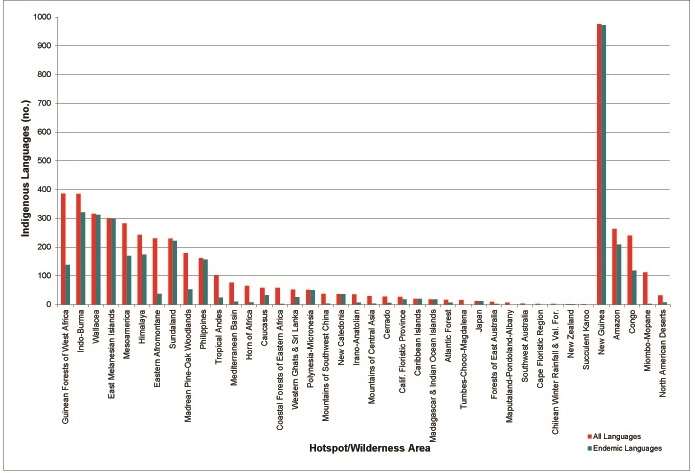

But when we examined the biodiversity hotspots and high biodiversity wilderness areas we found that of the roughly 6,900 languages spoken on Earth more than 4,800 occurred in these regions of high biological diversity (Gorenflo et al. 2012; see also Gorenflo et al. 2014). This co-occurrence was quite striking: nearly 70% of languages spoken on our planet occurred on about 25% of the terrestrial surface, the same areas where many of the species also occurred. The numbers of languages varied considerably, with smaller numbers tending to occur in biodiversity regions in temperate regions that had been colonized, mainly by Europeans, and experienced higher indigenous language loss (Figure 2).

Many languages were unique to the hotspots and high biodiversity wilderness areas—nearly 3,500, again varying by region (see Figure 2). And many of the languages were endangered, which in this study we identified by 10,000 or fewer and 1,000 or fewer speakers (Figure 3). About 2,800 of the languages occurring in the regions of high biodiversity had 10,000 or fewer speakers, while more than 1,200 languages had 1,000 or fewer speakers. Some hotspots like the East Melanesian Islands have more than 100 languages spoken by 1,000 or fewer speakers, including some with only a handful

of speakers, for example Araki and Mafea in Vanuatu. Similarly, the New Guinea Wilderness area, which has the greatest number of endemic languages, has more than 400 languages with fewer than 1,000 speakers, such as Kowiai and Saponi in West Papua, Indonesia. In the interest of examining co-occurrence of linguistic and biological diversity at a more refined geographic scale, we examined the presence of indigenous languages within the ranges of endangered amphibians and in protected areas in the regions of high biodiversity. Once again, the numbers were quite high: 68% of endangered amphibians occurring in regions of high biodiversity co-occurred with at least one indigenous language in those same regions, while 46% of the protected areas in those regions shared at least part of its geographic space with an indigenous language. Speakers of indigenous languages are well placed to engage in the conservation of certain species as well as many protected areas in regions containing much of the world’s biodiversity.

Why are the above results important? There are three reasons. First, co-occurrence of biological and linguistic diversity defines geographic priorities that appear to be important for the conservation of both nature and culture. Second, marked levels of linguistic diversity in most high biodiversity regions suggest some sort of relationship between indigenous languages and biological diversity, though presently we do not understand the reason for this link and it may vary among regions or localities within regions. Finally, if there is a connection between linguistic and biological diversity, a common (or at least coordinated) strategy for the conservation of culture and nature may also be possible. The possibility for addressing important cultural and natural conservation challenges in a limited number of localities using some sort of coordinated strategy seems important, particularly in a world rapidly losing diversity in both spheres, and where the successful conservation of one may well require the successful conservation of the other.

Opportunities to Conserve Significant Nature and Culture: UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Given the results of our earlier research, we began to seek evidence for where coordinated conservation solutions for biodiversity and language-culture might occur. It seemed that one approach would be to identify localities—protected areas—that hosted important natural content as well as indigenous language(s) and would attract considerable attention from any coordinated conservation efforts. We decided to examine World Heritage Sites (WHSs) defined by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Our focus was UNESCO WHSs defined based on their natural content, which we will call Natural WHSs. UNESCO defines Natural WHSs as reserves that contain physical or biological formations, habitat for threatened plant or animal species, or natural scientific, conservation, or aesthetic elements of outstanding universal value (UNESCO and Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, 2017). UNESCO also defines WHSs that contained mixed natural and cultural elements of outstanding universal value, and we included these sites as Natural WHSs as well. Natural WHSs possess high global visibility, thereby providing protected areas that could receive considerable attention were conservation actions successfully implemented that focus on both indigenous culture and nature.

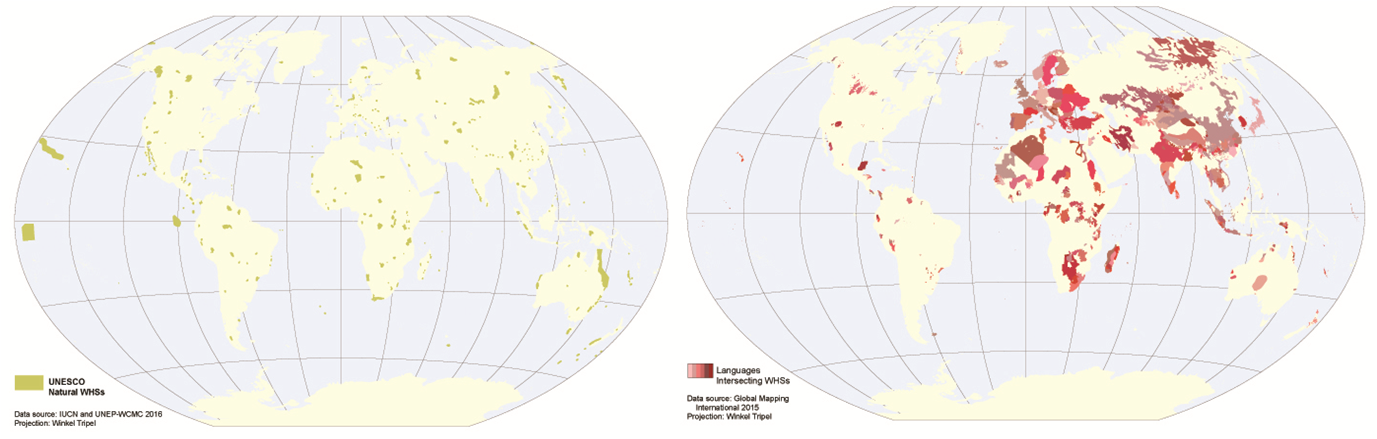

When we published a study on Natural WHSs in 2017, we examined indigenous language presence in the 238 Natural WHSs listed at that time, 203 based on natural content and 35 based on mixed natural-cultural content (Romaine and Gorenflo 2017) (Figure 4a). More than 78% of the Natural WHSs co-occurred with at least one indigenous language, and in all 445 indigenous languages shared at least part of their ranges with a Natural WHS (Figure 4b). Asia and Africa featured particularly large amounts of indigenous language co-occurrence with Natural WHSs, though co-occurrence occurred elsewhere as well.

We also examined Natural WHSs categorized as endangered by UNESCO, reserves under threat due both to ascertained dangers and potential dangers from a variety of causes (UNESCO and Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage 2017). And we examined languages in danger of disappearing, either due to reduced transmission from one generation to the next or to relatively small numbers of speakers, the latter criterion employing the same thresholds of 10,000 or fewer speakers and 1,000 or fewer speakers discussed above. UNESCO classified 18 Natural WHSs as endangered in 2017 (Figure 5a); we found that 90 indigenous languages co-occurred with these WHSs, most instances occurring in Africa and Asia (Romaine and Gorenflo 2017) (Figure 5b). Of those 90 languages, 13 were spoken by 10,000 or fewer, two were spoken by 1,000 or fewer, and 12 had reduced intergenerational transmission. For instance, Allar and Mannan, two languages that co-occur with the Western Ghats Natural WHS in southwestern India, both have limited inter-generational transmission (each classified under EGIDS as “endangered”) and are spoken by fewer than 10,000 people. Co-occurrences of endangered WHSs and languages mark high localities of particular importance, notably opportunities to conserve important places where nature or indigenous culture (or both) are under threat.

The results of this analysis themselves make a strong case for considering UNESCO Natural WHSs as localities where one might explore integrated conservation actions. In the 2017 paper, we suggested that the management of such high visibility sites would benefit from engaging local indigenous peoples, soliciting official input and guidance from the people(s) who are responsible, often, for the existence of these noteworthy reserves in the first place. We briefly discussed examples of involving indigenous people in the management of WHSs and other reserves in Australia, a nation actively engaging indigenous culture in protected area conservation.

Concluding Remarks

It is ironic in many ways that the incredible growth on Earth currently underway should be accompanied by disappearing diversity along several fronts. The decline in biodiversity is so rapid, and with such devastating potential, that researchers refer to these times as the sixth great global extinction (Barnosky et al. 2011). In contrast, some linguists reckon that at current rates of extinction 50-90% of the languages spoken on the planet will disappear by the end of the current century (Nettle and Romaine 2000). Such rapid disappearance of biological and linguistic-cultural diversity is shocking, and with a rapidly growing global human footprint due to an increase both in population and per capita demand will not slow in the absence of specific efforts to conserve both forms of diversity.

Our study of indigenous language occurrence in regions containing high biological diversity revealed that many of these areas host large numbers of such languages. If such co-occurrence indicates some sort of functional relationship, successfully conserving one form of diversity may aid in the conservation of the other. Joint efforts could occur in certain high visibility protected areas, such as UNESCO Natural WHSs. The majority of these sites host at least one indigenous language, in some cases many. Because of the national and international attention they receive, Natural WHSs likely would be eligible for more funding for expanded conservation efforts that seek to maintain both culture and nature. Moreover, conservation actions at such locations would receive international attention, helping to diffuse any evidence of successful coordinated conservation efforts to other localities.

Results of the research described above led us to seek solutions to managing protected areas that conserve both biological and linguistic-cultural diversity. One approach is to engage local indigenous people in the conservation of reserves. This strategy employs community conservation, an approach promoted widely over the past two decades as an alternative to more conventional, top-down conservation where a national or local government agency designs and manages protected areas, usually excluding local stakeholders. Involving indigenous people in managing reserves, probably through some sort of co-management scheme, would integrate invested local people who are key components of the ecosystems where those reserves occur. Maintaining those ecosystems presumably would contribute to maintaining resident indigenous cultural systems, possibly augmented by providing additional programs such as language revitalization to enhance cultural conservation further. Monitoring results on both biodiversity and cultural fronts will determine if this is an effective strategy, and if it is worth diffusing this solution from high visibility sites to other protected areas.

At UNESCO’s 43rd session of the World Heritage Committee in July 2019, indigenous peoples stressed that language is key to safeguarding World Heritage, conveying values and traditional ecological knowledge that can make site conservation and management more effective (whc.unesco.org/en/news/2013). The United Nations’ (n.d.) declaration of the International Year of Indigenous Languages in 2019 provides a timely, synergistic opportunity to integrate speakers of indigenous languages into standard planning and management strategies for World Heritage sites.

References

- Barnosky AD, Matzke N, Tomiya S, Wogan GOU, Swartz B, Quental TB, Marshall C, McGuire JL, Lindsey EL, Maguire KC, Mersey B, Ferrer EA. 2011. Has the earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature 471:51-57.

- Conservation International. n.d. Biodiversity hotspot and high biodiversity wilderness area geographic information system data. Conservation International, Arlington, VA.

- Global Mapping International (GMI). 2015. Global Mapping International, World language mapping system, Version 17. Global Mapping International, Colorado Springs, CO

- Gorenflo, LJ, Romaine S, Mittermeier R, Walker K. 2012. Co-occurrence of linguistic and biological diversity in Biodiversity Hotspots and High Biodiversity Wilderness Areas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109:8032–8037.

- Gorenflo LJ, Romaine S, Musinsky S, Denil M, Mittermeier R. 2014. Linguistic diversity in high biodiversity regions. Conservation International, Arlington, VA.

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and United Nations Development Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). 2016. The world database on protected areas (WDPA), July 2016. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK.

- Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, Brooks TM, Pilgrim JD, Konstant WR, da Fonseca GAB, Kormos C. 2003. Wilderness and biodiversity conservation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100:10309–10313.

- Mittermeier RA, Robles Gil P, Hoffmann M, Pilgrim J, Brooks TM, Mittermeier CG, Lamoreux J da Fonseca, GAB compilers. 2004. Hotspots revisited. CEMEX, Mexico City.

- Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J. 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403:853–858.

- Nettle, D, Romaine S. 2000. Vanishing voices. the extinction of the world’s languages. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Romaine S, Gorenflo LJ. 2017. Linguistic diversity of UNESCO Natural World Heritage Sites: bridging the gap between nature and Culture. Biodiversity Conservation 26:1973-1988.

- UNESCO and Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. 2017. Operational guidelines for implementation of the World Heritage Convention. World Heritage Centre, Paris.

- United Nations. n.d. 2019 International Year of Indigenous Languages. Accessed 10 August 2019. https://en.iyil2019.org/.

- Williams KJ, Ford A, Rosauer D, De Silva N, Mittermeier RA, Bruce C, Larsen FW, Margules C. 2011. Forests of east Australia. The 35th hotspot. In Biodiversity hotspots: evolution and conservation, edited by F.E. Zachos and J.C. Habel, pp.295–310. Springer, Berlin.

About Author :

L.J. Gorenflo1 and Suzanne Romaine2

L.J. Gorenflo1 and Suzanne Romaine2

1. Pennsylvania State University, United States of America [ljg11@psu.edu]

2. Oxford University, United Kingdom [suzanne.romaine@gmail.com]