Sumit Sarkar

Environmental activist, Bankura, West Bengal

Email: indsumitsarkar@yahoo.in

It’s now almost a decade ago while I was attending a seminar in relation to organic farming. There I came in touch with some legendary persons involved in organic farming. Ardhendu Shekhar Chatterjee was one of them. He had initiated an NGO, Development Research Communication and Services Centre, commonly known among organic farming enthusiasts of West Bengal as Service Centre. He was expressing his views this way: “anybody can become a farmer.” Those days I was working in a small publication institute but was thinking around that sometime I have to take some initiative such that I could develop a working model of practicing organic farming along with a sustainable lifestyle where one doesn’t have to depend too much on existing market system.

I actually started organic farming in a remote village in Jhargram District (earlier it was West Midnapur), wherefrom I gained my first experience of any sort of farming. That was a very enriching experience and this way I could understand that anybody CANNOT become a farmer. To become a farmer one has to gain a lot of skills. And those skills are gained by traditionally engaging in whatever farming activities are going on in a family or in a village. I also came to know that even someone living in a village may not know farming well and economic enough. It is because farming skillsare gained from almost teen ages.Actually it is gained even before that. One has to know the difference between ‘weeds’ and the plants that you are growing. If you spread different kinds of seeds in the same place, very often you will find that you don’t recognize which plant is going to yield what. But a skilled farmer knows it for certain. He/she knows the exact soil condition when to propagate any seed or when to till or whether to till or not, whether one should irrigate or not … and many more.

Every single step that I took and every lesson that I was gaining was by trial and error because nobody was teaching me directly. I was learning it by watching the activities of farmers. Again I was also creating some points of departure from their way of activities as mostly farmers in my vicinity were doing chemical farming. I was not using chemicals and that needed a lot of courage to do that because people would say that without Urea no paddy could be grown. When someone farming for years together says it, it does have some strong impression on your mind. But it was like a spoilt child of a family that I was doing organic farming in my own way, still gaining some knowledge from the neighboring villagers who were mostly farming paddy. I was trying all sorts of crops including pulses.

Field experience of the organic farming

During my city life, I used to be fascinated with the ideas expressed in the Fukowaka’s book One Straw Revolution. It inspired me to try natural farming without tilling the land. But throughout my  experience of farming I’ve never worked in a land that was never tilled or never do I farm without tilling at least once in a year. It is because grasses are the native varieties of land and if it is very thick, you may propagate some seeds there, some of them might even germinate and even grow within the periphery of dense grass but if you are looking for some kind of harvestable yield, that way of farming is not practical in most types of soil. Only if you are working in a loam soil in somewhat moist i.e., not too dry weather condition, one can practice no-till farming. I was lucky enough to work in that kind of loam soil while I was learning and practicing natural farming for the very first time. As that land was not owned by me, only my mother-in-law allowed me to farm there, it was compelling for me to till during monsoon cultivation i.e., paddy cultivation. However, I am sure that the land was appropriate enough to farm without tilling. Apart from that yearly tilling I was practicing natural farming techniques there such as spreading straws in the field after harvesting paddy etc. People would mock at me and name this straw-spreading activity as Kolkata Paddhati — “Calcutta process of farming.”

experience of farming I’ve never worked in a land that was never tilled or never do I farm without tilling at least once in a year. It is because grasses are the native varieties of land and if it is very thick, you may propagate some seeds there, some of them might even germinate and even grow within the periphery of dense grass but if you are looking for some kind of harvestable yield, that way of farming is not practical in most types of soil. Only if you are working in a loam soil in somewhat moist i.e., not too dry weather condition, one can practice no-till farming. I was lucky enough to work in that kind of loam soil while I was learning and practicing natural farming for the very first time. As that land was not owned by me, only my mother-in-law allowed me to farm there, it was compelling for me to till during monsoon cultivation i.e., paddy cultivation. However, I am sure that the land was appropriate enough to farm without tilling. Apart from that yearly tilling I was practicing natural farming techniques there such as spreading straws in the field after harvesting paddy etc. People would mock at me and name this straw-spreading activity as Kolkata Paddhati — “Calcutta process of farming.”

I found that in loam soils, if you spread seeds of Gram pulse over the straws spread over the paddy field, you will surely get some harvest. Later on, when I secured a land in Bankura district, western West Bengal, it was alluvial in nature. In such lands only during monsoon season and a few months after that, you have a comparatively cultivable situation beyond which soil becomes hardened like a rock. During spring time, and summer season if you irrigate enough and till it, you might succeed in creating a cultivable situation for a wider time span. This way you might get some crop, but it is a very expensive and water consuming activity I would say. So, in such soils, it is wise to cultivate paddy, pulses, or vegetables during monsoon only. Some people recommend saw dust to be spread  thickly over the land. Rather less expensive solution is mulching the land for years together. I am doing it in some parts of our land.

thickly over the land. Rather less expensive solution is mulching the land for years together. I am doing it in some parts of our land.

Let’s come back to the process of farming I was discussing about. I found that in most types of lands you have to till at least once in a year. If you are working in not so ideal kind of soil, that is if the land is alluvial or sandy or stony, you have to practice tilling whenever you want some harvestable crop. Another possible but expensive option is to trim the grass and spread whatever kind of seeds you are trying to propagate. This may not give you much harvest. Another very cheap and thus very popular method compared to one that I mentioned is spreading herbicides to control grass. I have to invest almost 15 thousand rupees per year to control only one weed — Kash i.e., Saccharum spontaneum. Simply tilling the land doesn’t serve the purpose for us because for the sake of extensive rain water harvesting we changed the landscape in a way that there are many small patches of land that cannot be tilled. Tilling can control grass but not Saccharum spontaneum. People do not give a heed that herbicides are fatal to nature and our own health, specially the farmers who are spreading it. It is mostly because, controlling Saccharum spontaneumby cutting it is too expensive as it spreads in geometric progression. Even tilling the land to control grass is considered to be waste of money. Actually entire social mindset is in favor of chemical farming. I find that if one cultivates in appropriate season and uses native varieties, extensive pest control doesn’t require. Here I am leaving alone eggplant. There’s no safe process of cultivating eggplant. Poisons are poisons – organic or not. If eggplant is cultivated safely, it always gets infected with insects. That insect infected Brinjal is good for health. You don’t get allergic attacks by eating it. This is my personal experience.

Chemical fertilizer also was accepted by farmers because it is a very cheap option. Specially, if you are using it in a traditionally cultivated land, it gives very good result. It is because the land is already rich with organic matters. Added chemicals are quickly absorbed by the long carbon chains present in the organic matters. But again it has an adverse impact on earthworms and other creatures living below the surface of land. Once a farmer starts chemical farming these creatures are killed. This keeps the land at the mercy of chemical inputs. But again people are slowly losing interest in keeping animals, specially cows, bulls and buffaloes. Reason being, firstly people don’t till with animals any more due to easy availability of tractors. Old cows are difficult to sell at good price as cow export by  illegal means to Bangladesh has stopped. This way there is very shortage of cow manure. Earlier I used to buy 600 rupees per trolley of tractor, now they are asking 900 rupees for that. I use cow manure. But it is not even a good quality manure in proper sense to the term. It is only stock pile of cow dung. Mixing cow dung with plant waste and turning it at regular interval and protecting the stock from heavy rainfall etc. are not practiced by any villagers as far as I could notice. I also am keeping animals but failing to do such regular jobs due to lack of helping hands in my family. So seems the case with other family too add to it that they don’t even find it very necessary for the nourishment of soil.

illegal means to Bangladesh has stopped. This way there is very shortage of cow manure. Earlier I used to buy 600 rupees per trolley of tractor, now they are asking 900 rupees for that. I use cow manure. But it is not even a good quality manure in proper sense to the term. It is only stock pile of cow dung. Mixing cow dung with plant waste and turning it at regular interval and protecting the stock from heavy rainfall etc. are not practiced by any villagers as far as I could notice. I also am keeping animals but failing to do such regular jobs due to lack of helping hands in my family. So seems the case with other family too add to it that they don’t even find it very necessary for the nourishment of soil.

Another issue that one should take into account, especially in West Bengal is that whether your land is ideally suited for paddy cultivation or not. Very often I find that farmers of our state, including our village, are most obsessed with paddy cultivation. They would leave no soil unturned to convert the nature of land such that it could become suitable for paddy cultivation. But in higher lands it is better if one cultivates millets, and pulses during monsoon. That is what I started to do in our land. At first I did it without tilling. Yield was satisfactory. Next year onwards the land was filled with thick grass. It was due our extensive rain water harvesting. We did it extensively along the contour lines and planted trees beside it. Nowadays due to such intensity of native grass, we have no other alternative but tilling the land. After tilling, we cultivated potato and other vegetables and oil seeds there for two years. Yield was satisfactory. But this year there being too much rainfall, we failed to grow any millet or pulses though we had to till the land before monsoon to arrest the growth of grass there.

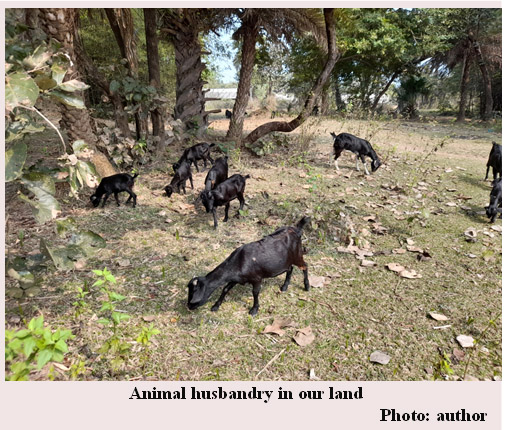

Animal husbandry, a popular side job or alternative to the mainstream cultivation practices has its own downside too. For the last two years I am doing animal husbandry. As a result, I had to stop farming vegetables, pulses and oil seeds near their sheds. As we are living in a comparatively isolated place, main village being at a little distant, our poultry birds are growing very quick without any  incidence of viral or bacterial attack. Goats are also doing comparatively better except during winter season. But we are failing to engage any person permanently or partially for looking after goats. Such jobs have become unattractive nowadays. Hence at times it becomes very stressful for a small family of four like us, to maintain the animals without any helping hand. We are keeping 30-40 chickens and around 20 goats. It at least is giving us some return, though it is still not at all close to bearing our family expenses. All the other farming practices that we do give us negative return. Another thing we learned is that if we keep more than 30/35 chickens, they roam so far and wide that often our roaming village boys, hunt these chickens by laying traps. We have to keep our one side of brain always in alert mode to avoid loss. However, considering my harrowing experience in organic mode of agriculture practice, I find animal husbandry to be easy, less expensive and comparatively sustainable way of doing things.

incidence of viral or bacterial attack. Goats are also doing comparatively better except during winter season. But we are failing to engage any person permanently or partially for looking after goats. Such jobs have become unattractive nowadays. Hence at times it becomes very stressful for a small family of four like us, to maintain the animals without any helping hand. We are keeping 30-40 chickens and around 20 goats. It at least is giving us some return, though it is still not at all close to bearing our family expenses. All the other farming practices that we do give us negative return. Another thing we learned is that if we keep more than 30/35 chickens, they roam so far and wide that often our roaming village boys, hunt these chickens by laying traps. We have to keep our one side of brain always in alert mode to avoid loss. However, considering my harrowing experience in organic mode of agriculture practice, I find animal husbandry to be easy, less expensive and comparatively sustainable way of doing things.

Here I would like to mention one additional but important fact that successful agricultural practice in traditional agrarian society like ours often depends on local socio-political milieu. Majority of our faming and accessory activities are dependent on our multifaceted relations with neighbors/local community. The positivity or negativity of this relation reflects on whether or not neighbors are stealing the harvest, poisoning of the water body, obstructing or helping in seasonal construction activities, whether acquiring manpower is easy or not and so on. Therefore, it is not only land, seed, water or fertilizer, the entire rural society is involved in agriculture. However, a large section of young villagers is trying to disassociate themselves from agriculture and becoming migrant labourer in search of little more sustainable income resulting in serious demographic change in our towns and villages as well.

Economic and political dilemma in organic farming practices

This way, I am no more a natural farmer as our land condition is not so suitable for no-till farming. But I am still holding on to organic farming though it is not very economical as it is very labour intensive a method. However, apart from economic issues, there are other considerations also that one has to look into. One needs to get some food from their own land because there is no guarantee that you can get organic foods if you are not growing it yourself. No matter wherefrom you are getting any organic crop, there is hardly any guarantee that it is truly cultivated in organic manner. Often people who are known to be organic farmers do organic farming in their land but to meet the demand of people who are asking for any kind of organic food, they ask other people in their village, to farm it. They may request them to do it without chemical inputs, but as far as my experience is concerned, I find that only very religious kind of dedicated persons do organic farming for their own consumption. Organic farming to succeed and to be implemented by wider section of farmers, a certain economic and social condition is required. That kind of situation don’t exist in our mainstream society any more.

It is because people are farming to get money. Now every crop is cash crop. Farmers need money to get all the things that consumers of food find it necessary for their own need. Money is the only driving force, whether any food bought from market is healthy or not is no more an issue. I have seen many paddy cultivating farmers who harvest paddy and sell it immediately and with the help of that money they buy rice from grocery shops or from MR shops. To sustainably get more cash by farming paddy, you have to sell more paddy and at a good margin of profit. But entire world agricultural economy is designed by certain corporate hands in a way that you can almost never make good profit out of farming.

Let’s take the case of mustard cultivation. Let alone West Bengal, even in Northern states of India, where Capital intensive farming is the norm, government don’t buy the mustard harvest at Minimum Support Price. Now Adani is importing mustard from abroad and we are purchasing it at doubled price within a year. It is Adani who stands to benefit, farmers remain satisfied with whatever little price they get from market (Vyas and Kaushik 2020). In our locality in Bankura there used to be more than six oil mills within a single small town. They used to purchase mustard harvest from north Indian states and mill them to produce oil. Now such mills are struggling to continue production. Apart from 2/3 mills most of them have closed production.

Now that in West Bengal, overwhelming majority of farmers are cultivating paddy with minimum machine input is a well-known fact, there should be no surprise in understanding that even if paddy could be sold at the government declared rate that would have implied less profitable compared to northern states of India. Only a handful of farmers here can sell their paddy at minimum support price. Rest of them sell it at 40% less rate to local business persons.

When this is the case with green revolution technology adopted chemical farmers, and the industries dependent on them, it is not hard to understand why people don’t do organic farming in mass scale. In the best case scenario, if you provide the farmers any indigenous seed, and assure them to buy the crop from them, they might farm it but will always use some chemical fertilizers, pesticides, etc., no matter how much you insist them not to do so. Most of the farmers are more confident about doing their farming in conventional manner with chemical inputs because it guarantees them certain amount of yield and they sell it at whatever price they get. By “whatever price” I certainly don’t mean that the price they get is whatever they wish, rather it means that they have to agree to sell their crop at whatever price option they are offered to. This way they are selling it at less than the cost of production for many years now. If you farm any crop without chemical input, cost of production being more, final output is going to be even costlier. Now consumers habituated with buying rice at low cost, as businessmen could buy paddy a lower rate from farmers, they find it too surprising to know that organic products are so costly. Apparently, sweet dreams of green revolution are over but future of organic farming is even dimmer.

As you see, there are so many limitations that one can do in organic or natural farming in today’s context. The time and place we are in impose some restriction on what can be done and what actually is possible. Unless we can convince a sizable number of people, I mean at least a few families who live close together and who have their farm lands side by side, we cannot expect enough yields and enough variety of crops growing in any small region. There are only a few communities such as Tili, Chasha etc. who are experts in vegetable farming. They are the most ideal community who could spread organic farming in their locality. They have the potential of resisting corporate onslaught on agriculture.

Yet there are no farmers’ organizations of such farmers in West Bengal. However, there are too many peasant ‘mass organizations’ of every single political party. Such pseudo-farmers ‘organizations basically act as subordinate branches of their respective political parties. This being the fact, they have failed to organize any serious movement to highlight their issue and bargain with governments. They have remained the crowd pullers of their political patrons. Unfortunately, these political patrons have no constructive approach or vision about agriculture.

Earlier during seventies there used to be a significant mass up rise of mostly landless peasants. As a result of which many vested lands, forest lands, and land of large land holders were distributed among individual ‘landless’ peasants. How much land did those landless peasants get? Very rarely a few acres. Mostly they received around a few bighas and even a few decimals of land. There was no other mentionable financial help. Neither was there much of vision or planning to achieve local level self-sufficiency. Agriculture cannot be practiced with land only. Those days, sharecropping used to be practiced along the length and breadth or our state including our neighboring states. Such sharecroppers or peasants who have limited land and other recourses cannot dare to experiment with their farming activity. They will not even be allowed to do so. They will not be allowed to make any long term planning related to the land they are allowed to cultivate. As a result, we hardly find any organic farmer who is a sharecropper. Let alone sharecroppers, marginal farmers, i.e., farmers who own less than an acre of land are almost never found to practice organic farming. They have no capital to speak of, no sufficient government support or any far-sighted plan to sustain yearlong on the land they own. Never did they try to organize them to collectively own farming tools or machineries. NO sweet dream can be dreamt of on the small and scattered patches of land that are characteristic feature of our countryside. No political party could gather courage to clean these Augean stable. It is the corporate houses who are seeing opportunity in it. It will be them who will be organizing these jigsaws puzzle-like patches of land.

Recently a large section of potato cultivating farmers came under the fold of Corporates in Burdwan, Bankura, West Midnapur districts of our state. They will be cultivating pepsi aalu as per their contract with this corporate house. Other corporate bodies have already started constructing their food storage silos in West Bengal. They have set their eyes on vegetable producing farmers of our state, the only potential force who had the skill to resist corporate control over agriculture.

As we see it, we are almost certainly approaching a suicidal situation in agriculture. Present way of farming is no more profitable. Neither is it good for ecosystem of farmland and health of people. The corporate houses have gained a lot of access over agriculture in West Bengal and other states. They are operating in a large scale with a lot of capital input. They have started working in developing their network and infrastructure to bring everything under control. Already there is a law in our state legalizing contract farming. Whereas in our state we have very small patches of land scattered here and there.

Now, our options are limited. I consider that those who have comparatively larger amount of land should concentrate on perennial plants farming instead of cultivating grains in large scale. It could be fruit trees or any other perennial trees that are of local use such as bamboo, fiber growing plants etc. Such plants don’t need extensive tilling or any other human input.

Unless we convert to that direction, I have every doubt if the farmers would be able to maintain control over their own land for long. Either they have to surrender before the corporate houses or have to turn their energy and labour toward animal husbandry and perennial plant growing. This is what I am concentrating on in my own land.

Earlier there used to be artisans such as weavers, potters etc. living in the village and doing their artisan activities. They would get some share of harvested crop in exchange of the services they give to the farmers. This way various artisans and farmers created ecological harmony and economic viability as well. Those days, farmers could manage their affairs with the help of these artisans living in their periphery in the same village or somewhere near it. This situation does not exist anymore. Both the weavers (and other artisans) and farmers have turned to market and both have lost their capital there. Neither farming activity nor various artisan activities are generating enough income to sustain their respective families. Factory level production has driven all kind of artisan activities on the brink of their extinction.

Conclusion

Capital has been flowing in to agriculture for many decades now. In the resent years it has accelerated in an unprecedented scale. It’s now two years since harvester is working overtime in paddy fields in as remote villages as our locality. Potato growing belts are witness to it for even more years. This year potato sowing is being done by machines. In no time harvesting also will be done by them. Agricultural labourers will be the hardest hit community in our villages.

Capitalism is knocking at our door steps. Organic farming will not be any fort to resist it given the situation we are thrown into. It’s not the capitalists rather our own lack of vision is to be blamed. Without a society in harmonious relation with nature there can be no ecological farming.

Reference

1) Vyas B.M. and Kaushik M. (2020) How India was stripped off its Atmanirbharta in the edible oil industry. https://thewire.in/political-economy/india-edible-oil-self-sufficiency