Prisha Tiwari

Department of Biology

Shivranjani Kumari

Department of Psychology

Ashoka University, Haryana, India

E-mail: prisha.tiwari_ug22@ashoka.edu.in

shivranjani.kumari_ug22@ashoka.edu.in

Stories from the Past: A Brief History of the Asiatic Lions

Even though the Royal Bengal Tiger steals the spotlight for most funding and conservation efforts in India today, a few decades ago it was the majestic Panthera leo persica or the Asiatic Lion (Fig.1) that was considered to be the pride of the Indian Subcontinent. Spanning from Sindh to Jharkhand, lions were found in large numbers across the country. However, by the turn of the century, large scale hunting led to the extinction of lions in all states except Gujarat. It was the animal-loving Nawabs of Junagadh who established laws against the shikaar of lions as early as 1879 and preserved their dwindling populations (Haraniya, 2018).

The first official wildlife conservation programme for Asiatic  Lions was started in 1965 by the Indian Forest Department by the establishment of a designated protected area. With successful implementation and management, there was a commendable rise in the lion population – from 177 in 1968 to 359 in 2005, and most recently around 674 in 2020.

Lions was started in 1965 by the Indian Forest Department by the establishment of a designated protected area. With successful implementation and management, there was a commendable rise in the lion population – from 177 in 1968 to 359 in 2005, and most recently around 674 in 2020.

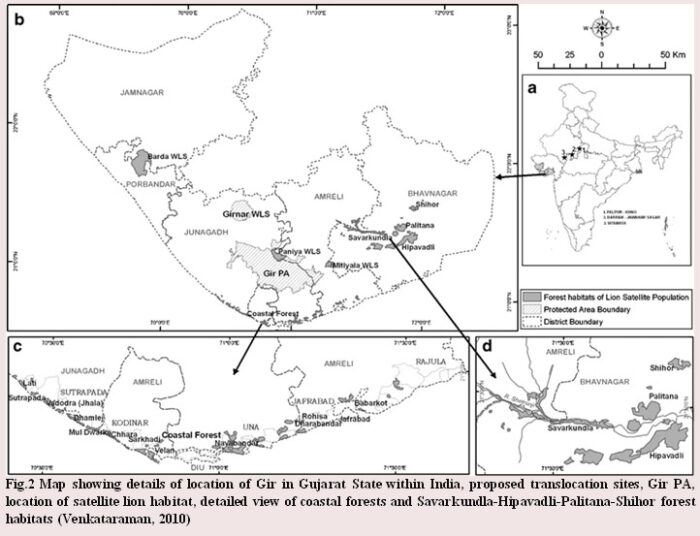

However, this good news comes with its own perils. With a rise in population, the lions now face a paucity of space and resources. They have expanded their territory and move throughout the Greater Gir landscape including 1,880 sq. km of the Gir Protected Area (GPA) and neighbouring satellite areas such as the Girnar Wildlife Sanctuary, human-dominated agro-pastoral districts of Amreli, Bhavnagar and Junagadh and some coastal areas (Dutta, 2015) (Fig.2). Although this comprises nearly 9,000 sq. km of land, in all, it is still considered to be a single population of lions. This introduces a plethora of problems for the species (Meena et al., 2014). Biologically, it’s not suitable for the only surviving population of Asiatic lions to be living in such a restricted area as it increases the probability of the entire population being wiped out in case of an epidemic or a natural calamity. A small and similar gene pool makes the whole population susceptible to the same kind of maladies and also reduces genetic diversity through inbreeding. For instance, in 1994, hundreds of lions in the Serengeti lost their lives to an outbreak of Canine Distemper Virus (CDV). Conservationists predicted that something similar might happen to the Asiatic population and that this might lead to the extinction of the species given its smaller size and habitat (Aggarwal, 2018).

Conservation Status and Management Planning

According to the IUCN Red list, the Asiatic Lion is listed as endangered due to the small size of its population and area occupancy. It is also listed in Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 with highly endangered animals such as the Caracal and the Dugong. The highest level of penalties is prescribed to individuals who commit offences on animals in Schedule I and II of the Act. The Asiatic Lion is also cited in Appendix 1 of CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) (World Wildlife Fund).

Plans to translocate the lions to geographically distant parks have been discussed for decades now. The first Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) was done in 1993 to look at potential habitats in Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. The census of the PHVA workshop was that lions needed to be translocated as soon as possible while maintaining strong efforts to protect them in Gir. In the end, the Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary was chosen as the most suitable habitat for reintroduction (Ashraf et al., 1995).

Based on this decision, the Lion Reintroduction Project came into existence and a committee was set up by the Indian Government to oversee the reintroduction of lions to Kuno. A three-phase plan which included – (1) Phase 1: from 1995-2000 during which 24 villages would be shifted out of the sanctuary, (2) Phase 2: from 2000-05 during which translocation would take place and the site would be electrically fenced, monitored and researched, (3) Phase 3: from 2005-15 which would focus on eco-development of the region (Johnsingh et al., 2007).

The first obstruction to this project came in 2004 when the Gujarat government refused to provide lions for translocation. By this time approximately $3.4 million had already been spent to relocate the villages from the Kuno Palpur Sanctuary. The issue was heavily politicised and the Gujarat government provided various arguments against translocation of the pride (Mitra, 2005). In response to the refusal by the Gujarat Government, the Centre for Environment Law and WWF filed a petition to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court only passed a verdict on the same in 2013, permitting the reintroduction of lions to Kuno and over-ruled the objections by the Gujarat government. While the Gujarat government tried to file another petition to the Supreme Court in 2014 to revoke its judgement, the petition was dismissed again by the top court. As of 2018, Gujarat had still not released any lions for reintroduction.

However, in 2018, this issue came under intense scrutiny as 23 lions died simultaneously in Gir National Park, out of which 5 were identified with the Canine Distemper Virus (The Hindu, 2018). In response to this, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change issued a statement launching the Asiatic Lion Conservation Project for a span of 3 years. The project allocated approximately Rs. 97 crores for state-of-the-art instruments, research, disease management, surveillance and patrolling techniques (Press Information Bureau, 2018). There were still no updates on the status of translocation.

In 2020, Prime Minister Modi announced the launch of Project Lion, which is modelled after Project Tiger and Project Elephant. The project identifies 6 new sites besides Kuno for lion relocation to combat the low genetic diversity in the lion populations by creating other free-ranging populations. However, the possibility of translocation of lions to these sites still seems far-fetched (Sharma, 2020).

Socio-political Dilemmas and People’s Involvement in Conservation Work

Since the1880’s, when Asiatic Lions went extinct from all over the subcontinent except Gujarat, the population of Gujarat has attached a sense of pride and belonging to the Asiatic lion. They have accepted them as a rudimentary part of their lives and ecosystems. Meena et al. (2014) looked at the human perceptions of lion conservation in each village of the GPA region. They interviewed 20% of the households in each village and assessed their responses to examine the villagers’ utility of the forested habitats in the GPA region, their attitudes towards lions, how the lions impacted crop-raiding wild herbivores and the mitigation efforts made by Gujarat State Forest Department. The results showed that out of all the respondents, only 2% of them identified the forest as a source of economic losses such as depredation. 40% of them, who identified as farmers, believed that the presence of lions deterred wild herbivores and free-ranging domestic stock from crop-raiding. But the most interesting responses were to the question of translocating lions away from the vicinity of villages – out of the 944 responses, only 20% were negativistic and wanted the lions to be translocated away from villages because of fear and feelings of mistrust. The rest believed that lions should not be translocated for various reasons. 31% of them believed that having the king of the jungle in their state was a matter of regional pride, suggesting a sense of affection towards the lions, along with a sense of belonging. 23% had eco-logistic reasons in mind and considered that translocation may disrupt the existing balance and harmony in the ecosystem. Some (10%) were concerned about the safety and rationality of disturbing lions from their current habitat, while around 14% did not support the relocation due to the functional purposes the lions served (such as reducing the presence of crop-raiding herbivores). A very small percentage (nearly 2%) had moralistic reasons to oppose the translocation and wondered if this decision aligned with the moral values they held (Meena et al., 2014). Overall, this shows that the people of Gir have a very positive relationship with the lions, even though some of their reasons for this might be misguided. This is in contrast to the government of Gujarat, whose relationship with the lions can be described as purely proprietorial. The protests in 2013 (Times of India, 2013), condemning the decision to translocate lions, was also a clear indicator of the dearth of knowledge and information that exists amongst people who are farther away from the animals in question.

Despite a direct order from the Supreme Court, the Lion Relocation Project was never implemented successfully. It was easier to relocate tribal villages in Madhya Pradesh than to get the government of Gujarat to part with some of its lions to ensure their long-term survival as a species. In 1996, when the minister for environment and forests reached out to the then Chief Minister of Gujarat, Narendra Modi, to shift two lions to implement phase two of the Relocation Project, neither did the Gujarat government respond, nor did the ministry follow up, resulting in a deadlock (Dutta, 2015). Many conservationists have raised concerns about how the survival of a whole species is hanging by a thread because of political benefits and Gujarat’s brand value (Aggarwal, 2018).

Associated Conservation Debates

An interesting twist in this debate is the reintroduction of Cheetahs that is planned for later this year. According to the reintroduction project, Cheetahs are being brought from Namibia and South Africa to the Kuno Palpur Wildlife Sanctuary. The Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary was declared a suitable habitat for Cheetah reintroduction in 2010 but the project was stayed by the Supreme Court as the sanctuary was supposed to be reintroduced with lions according to its 2013 orders. Eventually, the 2020 green signal for the reintroduction of cheetahs was given by the Supreme Court even though its previous order on Asiatic lions is unimplemented (Sreedhar, 2021).

Many have raised their concerns about the government undertaking this project at this point in time, when there are so many other pressing wildlife and conservation issues to address. Introducing a big cat to an unfamiliar landscape is an extremely complex challenge, and to do it when big cats that are indigenous to the country are in a precarious position themselves has raised a lot of criticism. This project will also take time, attention and resources from other conservation projects.

Although there is no logical or ecological justification for the push towards Cheetah reintroduction to the country, many claim that the casual shifting of attention from lions to cheetahs is fuelled by multiple political motives. The cheetah project is being projected as an effort to bring back the fastest cat in the world to India and resurrect it from extinction, thereby boosting national pride and identity (Srivastava, 2021). The bringing back of the fastest animal on Earth to this country would attract widespread attention and acclamation for the ruling government. Senior MoEFCC officials have hinted that lion translocation will probably not take place under the tenure of Prime Minister Modi. Actions regarding it will move at an extremely slow pace or won’t move at all to avoid antagonization.

There is a clash of priorities about which animal should be brought to Kuno first, keeping in mind that crores have already been spent on Kuno as a part of the Asiatic Lion Reintroduction Project. Quoting noted environmental lawyer Ritwick Dutta, “It is a classic case of misplaced conservation priorities. It is ironic that we want to shift our whole conservation focus on a species that went extinct in the 1950s rather than those which are on the verge of going extinct in a few years.” (Aggarwal, 2020)

Resolution of the Issue

The translocation of Asiatic Lions has been complicated by politicisation and the lack of coordination of concerned bodies in a federal structure. However, if the last remaining population of lions is to be conserved in the long-term, translocation is the best solution at hand. The issue can be addressed by trying to raise awareness amongst the natives of the Gir Protected Area to highlight the urgency of relocating lions. We can also consider translocating Asiatic lions from zoos and other enclosures outside Gujarat to circumvent dealing with an obstinate Gujarat government. The issue deserves more media attention not only to garner widespread public support, but also to ensure that the cause is not lost amidst other on-going projects like the introduction of Cheetahs. More pressure to resolve this issue can only come from the public and top court. Communication strategies need to be devised to associate the Asiatic Lion not just with state pride, but with national pride as well. Such messages will help elicit more attention from the public on the issue and create a sense of collective responsibility towards these majestic animals.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Balaji Chattopadhyay and Kritika Garg for their constant guidance and support, and for facilitating this publication. A special mention to Divya Karnad for motivating us to pursue this topic and giving us valuable ideas pertaining to wildlife conservation in India.

Reference:

1. Aggarwal, M. (2018). How politicking and state apathy has put the survival of the Asiatic lion at risk in India. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/876349/how-politicking-and-state-apathy-has-put-the-survival-of-the-asiatic-lion-at-risk-in-india

2. Ashraf, N., Chellam, R., Molur, S., Sharma, D., & Walker, S. (1995). Asiatic Lion – Population & Habitat Viability Assessment. URL: http://www.cbsg.org/sites/cbsg.org/files/documents/asiatic_lion_phva_%281993%29.pdf

3. Dutta, R. (2015). Reintroduction of the Asiatic Lion. Economic and Political Weekly, 54(22),7–8. URL:https://epw.in/journal/2019/22/commentary/reintroduction-asiatic-lion.html?0=ip_login_no_cache%3D735f0ae027d53603f8b95092baa8ef51

4. Haraniya, K. (2018, September 9). How the Gir Lions Were Saved. Live History India. URL:https://www.livehistoryindia.com/story/snapshort-histories/how-the-gir-lions-were-saved/

5. The Hindu. (2018, October 5). Canine Distemper Virus (CDV) found to be cause of death in Gir lions. Business Live. URL:https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/canine-distemper-virus-cdv-found-to-be-cause-of-death-in-gir-lions/article25135167.ece (Retrieved 02/12/2021)

6. Johnsingh, A., Goyal, S., & Qureshi, Q. (2007). Preparations for the reintroduction of Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica into Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary, Madhya Pradesh, India. Oryx, 41(1), 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0030605307001512

7. Meena, V., Macdonald, D. W., & Montgomery, R. A. (2014). Managing success: Asiatic lion conservation, interface problems and peoples’ perceptions in the Gir Protected Area. Biological Conservation, 174, 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.03.025

8. Mitra, Sudipta (2005). Gir Forest and the saga of the Asiatic lion. Indus Publishing. pp. 226–227. ISBN978-81-7387-183-2. (Retrieved 02/12/2021)

9. Press Information Bureau. (2018, December 20). Government Launches Asiatic Lion Conservation Project [Press release]. https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=186688

10. Sharma, R. (2020, August 16). “Project Lion” for Conservation of Asiatic Lion Announced, Translocation Pending. The Indian Express. URL:https://www.newindianexpress.com/thesundaystandard/2020/aug/16/project-lion-for-conservation-of-asiatic-lion-announced-translocation-pending-2183915.html (Retrieved 02/12/2021)

11. Sreedhar, N. (2021, October 23). The Cheetah is Returning to India but at What Cost? Mintlounge. URL:https://lifestyle.livemint.com/smart-living/environment/the-cheetah-is-returning-to-india-but-at-what-cost-111634930765574.html (Retrieved 02/12/2021)

12. Srivastava, S. (2021, January 26). India’s Cheetah reintroduction plan is fraught with political symbolism, short on scientific rigor. The Swaddle. URL:https://theswaddle.com/indias-cheetah-reintroduction-plan-is-fraught-with-political-symbolism-short-on-scientific-rigor/ (Retrieved 02/12/2021)

13. Times News Network (2004, 2 September). “Gir will be lions’ only home: Gujarat”. The Times of India. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. (Retrieved 02/12/2021)

14. Times of India. (2013, April 13). Gujarat: Protests against SC’s decision to shift Gir lions | News – Times of India Videos. The Times of India. https://m.timesofindia.com/videos/news/Gujarat-Protests-against-SCs-decision-to-shift-Gir-lions/videoshow/19583701.cms

15. Venkataraman, M. (2010). ‘Site’ing the right reasons: critical evaluation of conservation planning for the Asiatic lion. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 56, 209–213. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-009-0344-6

16. World Wildlife Fund. (n.d.). Asiatic lion. WWF India. URL:https://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/priority_species/threatened_species/asiatic_lion/ (Retrieved 03/12/2021)