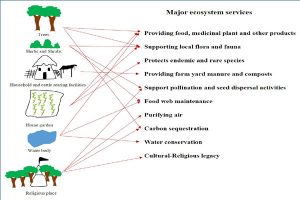

Hydro-Hegemony: The weaponization of water

Our introduction to water is as old as our existence. The human civilization started its journey in full swing once our ancestors settled along the riverside for the sake of agriculture. Since then, it was a long course  of actions centering around water which redefined our economy, politics, culture, and society. Along with all its boon, water is also a powerful weapon for those who believe in hegemony irrespective of justice, logic, and humanity. Transboundary rivers are burning examples of the powerful tussle among the nations and often the problem tends to shape the regional geopolitics. Noted examples can be drawn from the middle east countries around the Tigris-Euphrates river basin, and South east Asian countries around Mekong river basin.

of actions centering around water which redefined our economy, politics, culture, and society. Along with all its boon, water is also a powerful weapon for those who believe in hegemony irrespective of justice, logic, and humanity. Transboundary rivers are burning examples of the powerful tussle among the nations and often the problem tends to shape the regional geopolitics. Noted examples can be drawn from the middle east countries around the Tigris-Euphrates river basin, and South east Asian countries around Mekong river basin.

The Tigris-Euphrates basin spans across six countries including Iraq, Iran, Jordan, Turkey, Syria and Saudi Arabia. The river water is the backbone of the flourishing human settlement in the region. Along prosperity, water acted as key player to establish political supremacy in the region from historical past. It has both the use of weapon and target as and when required. Water related infrastructures like, pipelines, reservoir, pumping and distribution systems, sanitation are strategic targets for conflicting parties to suppress the opponents. Attacks on the Kuwait’s water supply and wastewater infrastructure (early 1990, first Persian Gulf war), capture of the Tishrin Dam on Euphrates river (November-December 2012, Syrian civil war), air attack on Raqqa city water plant and water supply system (November – December 2014) or destruction of desalination plant near Mocha, Yemen (January 2016) are few instances of targeting water for casualty. Similarly, intentional flood, disruption in agricultural and hydropower production and interruption in drinking water availability are few of the common war strategies rival groups follow to gain control over the area of interest.

The scenario is different in Mekong river basin in south-east Asia. Mekong, the 12th largest river on earth is originated from the Tibetan plateau of China and passes through Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and  Vietnam before reaching to the South China Sea. It is one of the richest biologically diverse river basins and life support for ~60 million people at the downstream countries. The conflict on sharing Mekong’s water started when China as an upstream country initiated mega dam projects on Mekong River for hydroelectricity generation, water storage and navigation. A total of 11 mega dams proposed on the Chinese side of the river already created a noticeable change in the availability of water in the downstream region during dry season. Apart from water, excessive dredging for navigation at the upstream region deprives the downstream areas of nutrient rich sediments essential for aquatic life and agriculture. These moves are alarming for the downstream countries as the hydro-hegemony over the Mekong seems to affect greatly the riverine ecosystem as well as livelihood of the people.

Vietnam before reaching to the South China Sea. It is one of the richest biologically diverse river basins and life support for ~60 million people at the downstream countries. The conflict on sharing Mekong’s water started when China as an upstream country initiated mega dam projects on Mekong River for hydroelectricity generation, water storage and navigation. A total of 11 mega dams proposed on the Chinese side of the river already created a noticeable change in the availability of water in the downstream region during dry season. Apart from water, excessive dredging for navigation at the upstream region deprives the downstream areas of nutrient rich sediments essential for aquatic life and agriculture. These moves are alarming for the downstream countries as the hydro-hegemony over the Mekong seems to affect greatly the riverine ecosystem as well as livelihood of the people.

Image: https://transboundarywaters.science.oregonstate.edu/content/tigris-euphrates-river-basin (Tigris-Euphrates river basin), https://www.conservation.org/places/greater-mekong(Mekong river basin)

Collector: Rajasri Ray

A tale of two leaves

Think desert plant, the spectacular variety of Cacti and Euphorbias pops out. We  know about their thorny leaves, green stem, deeper roots and even wonderful flowers, an all-out attempt to conquer environmental adversary. Well, Welwitschia mirabilis is a super adapter that deserves special mention. Named after Austrian botanist Friedrich Welwitsch, the plant was discovered in 1859 at Namib desert near south-western coast of Africa. Welwitschia is too much simple in structure compared to its existence on the earth. The name ‘living fossil’ is well suited due to its long term existence on earth since 113 million years and exceptionally long lifespan (~1500-2000 yrs.). It is a plant of a dwarf stem, two leaves and reproductive cones.

know about their thorny leaves, green stem, deeper roots and even wonderful flowers, an all-out attempt to conquer environmental adversary. Well, Welwitschia mirabilis is a super adapter that deserves special mention. Named after Austrian botanist Friedrich Welwitsch, the plant was discovered in 1859 at Namib desert near south-western coast of Africa. Welwitschia is too much simple in structure compared to its existence on the earth. The name ‘living fossil’ is well suited due to its long term existence on earth since 113 million years and exceptionally long lifespan (~1500-2000 yrs.). It is a plant of a dwarf stem, two leaves and reproductive cones.

Welwitschia is eye catching to onlookers for its leaves. They are unique due to their unlimited growth throughout the plant life, thanks to the basal meristem (growth tissue) present at their base. As the leaves grow in size (growth rate is 13.8 cm./year), the tip portion get old, and is torn apart into ribbon like pieces due to continuous abrasion against desert wind and sandy ground. All these strapped ribbon like portions coiled around the short trunk mimicking a messy green bush amidst the pretty hot desert landscape.

Despite the mere presence in numbers, the leaves play disproportionately large role in desert ecology. It is because of the length they are able to collect a good amount of dew from the morning fog and channel it towards the underground which eventually helps the plant to meet up the water demand partially. The long and thick coiled leaves create a perfect adobe for desert fauna especially during day time. They altogether create a shady and cooler environment for cape hares, snakes, agamas, geckos, skinks, spiders, scorpions and insects and a favorable spot for predators too. Moreover, desert bug, Odontopus angolensis gets its nutrition from the plant sap piercing it with its needle like beak. Similarly, Antelope and Rhinos also go for juicy leaves during food scarcity and humans are no less fortunate. Earlier, the core of the female plant was considered as a food for desert people, so the name ‘desert onion’. Considering the depauperate surroundings of the superarid Namib desert, a Welwitschia plant itself is a mini ecosystem surviving on its own.

Image : Rajasri Ray, www.info-namibia.com

Collector: Rajasri Ray

Amphibian Kharai Camels of Kutch

Domestication is a remarkable event that allowed humans to gain an unprecedented power to control their biological resources; the obvious outcome of which is reflected in the diversity of tamed animals and their numerous breeds. Some of these breeds are typically adapted to local harsh environmental conditions. Amphibian Camels aka Kharai Camels of Kutch are indeed a special group of animals which are powered with a unique ability to survive on both, dry land and in the sea. In the water, they are prolific swimmer unlike any other camel. It is also supported by their unmatched ability to feed on saline foliages of the luxuriant mangroves. In Gujarat’s Kutch district, primarily in four areas Abdasa, Bhachau, Lakhpat, and Mundra, these animals are painstakingly managed by the Jat community who are nomadic  camel herders for many generations. These camels are their means of subsistence and share a close relation of dependence with the herders in a rugged landscape full of hardship. In the arid regions of Kutch, the herders have to cover a long distance to look for mangroves for managing these camel herds. Sometimes they have to survive on camel milk for a few days until they are back to their homes.

camel herders for many generations. These camels are their means of subsistence and share a close relation of dependence with the herders in a rugged landscape full of hardship. In the arid regions of Kutch, the herders have to cover a long distance to look for mangroves for managing these camel herds. Sometimes they have to survive on camel milk for a few days until they are back to their homes.

Identifying their unique features, Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) distinguished the Kharai Camel as a separate breed in 2015. Moreover, FSSAI (Food Safety and Standards Authority of India) and AMUL (a milk operative) have recognized camel milk as nutritious and branded for its therapeutic properties in diseases like autism, TB, diabetes and even in cancers.

On the flip side, recent enumeration says the number of camels has been dwindling fast and only a few thousands exist. Thinning of supporting mangroves due to heavy industrialization and thus concomitant rise of maintenance cost are the primary causes of concern. Hence, the traditional herders find it really hard to make ends meet. The Kharai Camels have been declared as highly threatened by Government of India and conservations programs are in full swing to increase their population. Unfortunately, the efforts may be only a drop in the ocean. Unless the lifeline of the area – the lush green mangroves – are saved from imminent threats and managed healthily, the fate of Kharai Camels will be sealed along with the several other of inhabitants.

Representational Image, courtesy: By Jjron – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2831408

Collector – Avik Ray

Gundruk or fermented leafy greens

Fermented food stuffs of umpteen numbers have been quite popular across various parts of the world and commonly practised to balance resource crunch in lean season. Or put differently, these you can save  wisely at the time of plenty for later when there is not much in hand. Fermented leafy greens of India do not have many in their reserve. But the Nepali and Gorkha community of northern part of West Bengal and elsewhere evolved and fine-tuned their unique way of saving juicy and leafy foliage for off-season. Mustard greens or rayo or rai shaag are the main element, that could be accompanied by others, such as radish or cauliflower leaves or even fleshy underground roots. From which they prepare their signature fermented foliage or adorably called as ‘Gundruk’.

wisely at the time of plenty for later when there is not much in hand. Fermented leafy greens of India do not have many in their reserve. But the Nepali and Gorkha community of northern part of West Bengal and elsewhere evolved and fine-tuned their unique way of saving juicy and leafy foliage for off-season. Mustard greens or rayo or rai shaag are the main element, that could be accompanied by others, such as radish or cauliflower leaves or even fleshy underground roots. From which they prepare their signature fermented foliage or adorably called as ‘Gundruk’.

Mustard greens or Brassica juncea is one of their favourite crops which grows in abundance along with many others in sunny winter or pleasant summer of this region. Almost every household of the montane villages or foothills even with a small patch of land cultivate greens and the harvest is often far more than that can be consumed at a time. So, an elaborate process of processing through fermenting, drying and storing for leaner seasons has been evolved and perfected: the leaves are allowed to sundry for a couple of days followed by smashing, squeezing and tightly packing in closed glass jars for days for fermentation to takes place in  warm place. Lastly, slightly acidic fermented leaves are taken out and again dried under the sun. Although there are local variations suiting one’s taste the recipe remains more-or-less the same. And if moisture is prevented, Gundruk can be used for months so one can enjoy them during incessant rains as well as in chilly and foggy winter. Pediococcus and Lactobacillus species remain fully functional during the fermentation process – so says the underlying science.

warm place. Lastly, slightly acidic fermented leaves are taken out and again dried under the sun. Although there are local variations suiting one’s taste the recipe remains more-or-less the same. And if moisture is prevented, Gundruk can be used for months so one can enjoy them during incessant rains as well as in chilly and foggy winter. Pediococcus and Lactobacillus species remain fully functional during the fermentation process – so says the underlying science.

However, Gundruk is not merely a fermented food that supplements nutrition in hard times, it does have another spicier story. Mixed with heavy flavouring and seasoning agents, its tangy taste often lures taste buds and elevates one’s mood in soggy weather. Some even says it acts like magic when appetite dies after days of continuous fog or rains common in hills. A hot and peppy soup of mouthful of Gundruk (Gundruk jhol) aids in digestion and stimulates bowel movement. There is another avatar which is also a sought-after, i.e., its pickle called as Gundruk achaar, favourite among Nepali or Gorkhali diaspora.

Photo courtesy: By Krish Dulal – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30755190

Collector – Avik Ray