Aam-aadmi (The Mango people)

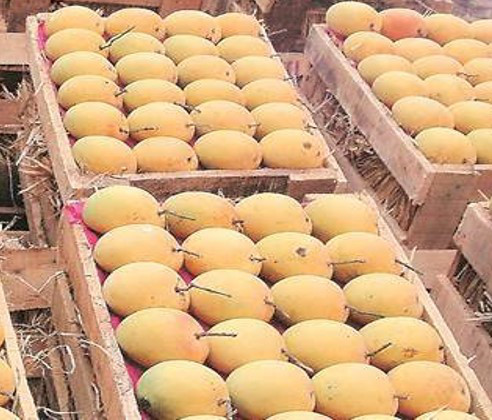

“Mango” word itself is one of the identifiers of India. This magical word entangles with countless stories, history, innumerable local landraces, sprawling economy, and regional competition, a summary formed of diverse social-cultural and economic network. Let’s listen to a great live story of “Migration for Mango” that cuts across international border. Our story starts in the coastal Maharashtra region especially, in Ratnagiri, Raigad, and Sindhudurg districts, famous for Alphonso mango or Hapus. Alphonso is considered the king of Mangoes in the commercial market and, it bears the Geographical Indication (GI) tag for the Konkan region of Maharashtra. Alphonso fetches a hefty amount of money, so, a prized possession for the orchard owners. However, like humans, Alphonso attracts monkeys, birds, and other animals, so mango season also a season of alertness for the farmers. Here comes the protector or Rakhwaldar, who takes care of the orchard on behalf of the farmer, and, in the Alphonso orchards, the job is for Nepali and Gorkha people who are seasonal migrants from Nepal. Their duties include, protecting the orchard from the wild animals, mango harvesting, sorting, packing, arranging, and transportation, a long 6-7 months’ affair. It is an approximately 2000 km journey for these Himalayan people to reach coastal Maharashtra from the bordering villages of Nepal. Each year, like our seasonal migratory birds, their journey starts in early to mid-November, passing through the Trinagar customs at the India-Nepal border, get the bus from Palia-Kalan (Uttar Pradesh) to reach Pawas in Ratnagiri. Orchard owners welcome these migrant laborers as cheap manpower with less demand, negotiable price, and worthy of reliance. This 6-7 month-long contractual job offers stable income for these marginalized people which eventually boosts the migration rally to a great extent. Nowadays, approximately 70,000 workers make this possible for their livelihood. On the flip side, no insurance, no medical benefit, no limit for the working hour are part of this mango duty. Over the years, conventional single male migration has been transformed into a whole family movement due to the requirement for essential domestic works like cooking and cleaning. Family migration eases the workload to some extent and assures some extra income but, instability still exists like kids’ education, adjustment with the local culture, language, etc. Despite all odds the migrant workers silently humming around the mango orchards to save the prized possession of the country. Like a true king, Alphonso of India ties a friendly knot with Nepal.

stories, history, innumerable local landraces, sprawling economy, and regional competition, a summary formed of diverse social-cultural and economic network. Let’s listen to a great live story of “Migration for Mango” that cuts across international border. Our story starts in the coastal Maharashtra region especially, in Ratnagiri, Raigad, and Sindhudurg districts, famous for Alphonso mango or Hapus. Alphonso is considered the king of Mangoes in the commercial market and, it bears the Geographical Indication (GI) tag for the Konkan region of Maharashtra. Alphonso fetches a hefty amount of money, so, a prized possession for the orchard owners. However, like humans, Alphonso attracts monkeys, birds, and other animals, so mango season also a season of alertness for the farmers. Here comes the protector or Rakhwaldar, who takes care of the orchard on behalf of the farmer, and, in the Alphonso orchards, the job is for Nepali and Gorkha people who are seasonal migrants from Nepal. Their duties include, protecting the orchard from the wild animals, mango harvesting, sorting, packing, arranging, and transportation, a long 6-7 months’ affair. It is an approximately 2000 km journey for these Himalayan people to reach coastal Maharashtra from the bordering villages of Nepal. Each year, like our seasonal migratory birds, their journey starts in early to mid-November, passing through the Trinagar customs at the India-Nepal border, get the bus from Palia-Kalan (Uttar Pradesh) to reach Pawas in Ratnagiri. Orchard owners welcome these migrant laborers as cheap manpower with less demand, negotiable price, and worthy of reliance. This 6-7 month-long contractual job offers stable income for these marginalized people which eventually boosts the migration rally to a great extent. Nowadays, approximately 70,000 workers make this possible for their livelihood. On the flip side, no insurance, no medical benefit, no limit for the working hour are part of this mango duty. Over the years, conventional single male migration has been transformed into a whole family movement due to the requirement for essential domestic works like cooking and cleaning. Family migration eases the workload to some extent and assures some extra income but, instability still exists like kids’ education, adjustment with the local culture, language, etc. Despite all odds the migrant workers silently humming around the mango orchards to save the prized possession of the country. Like a true king, Alphonso of India ties a friendly knot with Nepal.

Image: Indian Express

Collector: Rajasri Ray

Sustainability in space

Satellites are now a part of our lifestyle. Our communication life viz., social media, television, computer  is entirely dependent on them. There are currently ~6000 of them in space to tap the potential of the space communication system. However, a good percentage (nearly 60%) of these space machines are non-functional thus, creating space junk. Defunct satellites whole or their fragments (generated due to collision among the satellites) are a great source of danger for active satellites and pollution in space. Still, we are expecting new batches to enter in space duties in coming years, therefore, increment in space junk. Despite having initiatives like optimization of compactness, alternative fuel use, etc. a comfortable level of sustainable practice is yet to be achieved.

is entirely dependent on them. There are currently ~6000 of them in space to tap the potential of the space communication system. However, a good percentage (nearly 60%) of these space machines are non-functional thus, creating space junk. Defunct satellites whole or their fragments (generated due to collision among the satellites) are a great source of danger for active satellites and pollution in space. Still, we are expecting new batches to enter in space duties in coming years, therefore, increment in space junk. Despite having initiatives like optimization of compactness, alternative fuel use, etc. a comfortable level of sustainable practice is yet to be achieved.

Recently, one ambitious project has been announced from Kyoto University (Japan) jointly with Sumitomo Forestry (a logging company) to launch a wooden satellite in space to reduce the quantum of space junk. The proposed advantages are – they would have burned up without throwing out harmful chemicals in the outer space or raining debris on the Earth, wood is electromagnetic wave friendly so, act as a protection for antenna or other valuable instruments and cost-effective. The satellite may make its space debut in 2023 if everything runs well. However, the mission is full of challenges like, how the wood will be seasoned to reduce the internal moisture, what type of wood will be appropriate for use, the kind of design, etc. Whatever will be the result, the attempt to introduce sustainability beyond the Earth is something worthy for all of us.

Source and Image: BBC news, 29th December 2020

Collector: Rajasri Ray

The Mazri Palm – a culturally and economically tree – even porcupines love them!

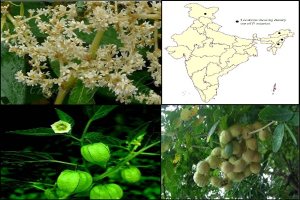

The Mazri Palm, Nannorrhops ritchiana, is historically entwined with the cultural and economic lives of the locales of Pakistan and adjacent states. The tree is one of the widely distributed native palm species of Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. Almost every part of the plant is usable and the products are equally diverse. The tough fibre obtained from leaves and stems serves as fine raw material for making a variety of household items like mats, fences, house roofing, and other handicrafts such as hand fans, baskets, brooms, trays, storage boxes, hats, and sandals. The diversity of the handicraft is also astounding; it tends to vary with the cultural geographic regions. The other plant parts are no less important, while the fresh fruits are edible, seeds are for manufacturing rosaries. Similarly, the dried parts of the plant are often used as Fuelwood and the reddish mossy wool of the petioles is utilized as tinder.

So, quite understandably has been its remarkable role in the livelihood of the local people that caused its over-harvesting for domestic and commercial needs and rapid decline of viable populations. In some places (such as in Hazar Nao Forest of Malakand region), the plant is reported to be on the verge of extinction due to overuse for commercial purposes. Regionally, it has been categorized as Endangered (EN) under the IUCN criteria. Hence, realizing its cultural and economic importance, the Government of Pakistan enacted the conservation of Nannorrhops in Pakistan in general and specifically in the Kohat Division (southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa).

Perhaps, its ecological significance has also been so overriding that its decline left mark on the other non-humans. Rapid erosion of its viable population kept the lives of other dependent fauna at stake. One of the key species affected is the Indian porcupine (Hystrix indica) which is endangered in the region. It grazes on the roots and leaves of Nannorrhops for food mostly in the lean winter. It is also joined by a species of a black bear that seemed to have disappeared in the recent past. Perhaps, many more visible and invisible faunal members have been in the list of the disturbed that direly necessitated the need for conservation and sustainable management of the palm tree in and around its native range. The threats remained largely undocumented, however. The conservation and sustainability initiative could restore its past biological and cultural glory. The story of the Mazri Palm once again reiterates the dilemma of human resource use and overuse and its impact on ecosystem health and function.

Image courtesy: Khan et al. 2020. Mazri (Nannorrhops ritchiana (Griff) Aitch.): a remarkable source of manufacturing traditional handicrafts, goods and utensils in Pakistan. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 16, 45 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-020-00394-0

Collector: Avik Ray

With boreholes, Pests in Prehistory, yes, indeed!

Agricultural pests, borers, suckers, hoppers, leaf-cutters or eaters, rotting-promoters, root-destroyers……. are ubiquitous today, from staple crops to non-staples to cash crops, they are

omnipresent. They make headlines quite often. They do appear in many avatars, from insects to molluscs to bacteria or fungi. Every now and then they wreak havoc in the agricultural systems causing major economic damage and raising farmers’ woes and worries. So are pesticides, fungicides, or larvicides, and their rampant application around the world, somewhere it is more whereas less in other places. Moreover, their unregulated and over-use is worrisome, and that has been a concern in many developing or developed countries.

Indeed, pests have been co-evolving with their host plants over their periods of biological evolution but may not have emerged as a menace. But, what about their threats in history or even further back in time, i.e., prehistory? It may not be of a similar scale and extent as modern times, but pests did have ancient links. Though scant, many of the stories of infestation go back to prehistory. It is where archaeologists have a larger role to play – they have been painstakingly unearthing hidden records of ravages by pests and joining the jigsaw pieces to tell us the pest stories from the distant past.

There are many such examples in the Neolithic, either in cereals or pulses, e.g., the marks of grain weevil or Sitophilus zeamais/oryzae on 9000 year-old potsherds have been discovered. Cases of wheat weevil (Sitophilus granarius) infestation in south-west Asia as well in Neolithic Europe; however, they are said to have largely disappeared around 4500 BC and only returned during the Iron Age. On the other hand, the earliest pest-infestation of fava beans displaying boreholes has been identified in Catalonia, Spain. The presence of pea weevil has also been detected in Switzerland.

Well, were the farmers aware of the pest attack? Yes, say the experts. So, what did they do to deal with this? They used to discard the infested seeds and offer those to animals as fodder. They even co-grown trap crops or insect repellent plants to ward off the pests, presumably.

Well, this may be a thin and small slice from the larger story. More research on this front can unveil remarkable facts about crop damage faced by our ancestors and how they might have responded to this crisis. Or was that really a crisis? Knowing its nitty-gritty could help us to find out the trajectory of our cropping systems, their pitfalls and resilience.

Image courtesy: By Sarefo – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2900877; By CSIRO, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35486312

Collector: Avik Ray