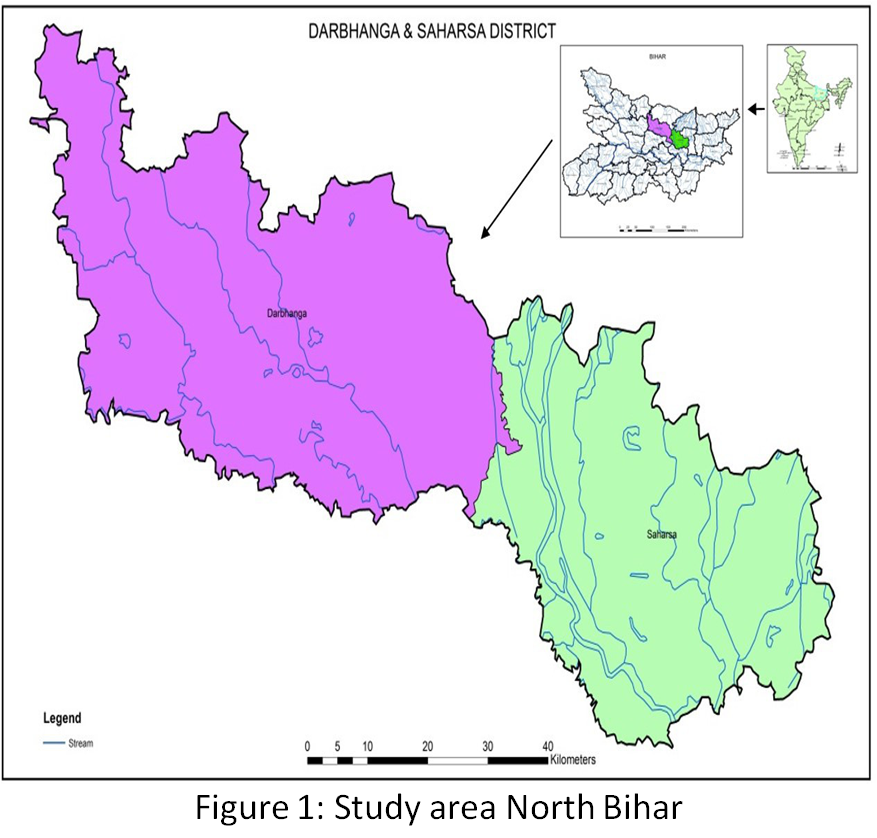

North Bihar is a flood-prone region and every village and Mohalla in this region is either bisected by small and big rivers flowing from the Nepal Himalaya or surrounded by ponds and wetlands locally known as chaurs.  The communities living in the Kosi villages are mainly dependent on agriculture and fishing. When there is no work at agricultural fields, men from most of the lower caste communities including Musahar and Mallah, two of the most marginalized communities, out-migrate for labour work in other states of India and to Nepal for selling ice-cream on a bicycle. The women live in the villages throughout the year somehow managing the family with money sent by their husbands and sons, they also work in fields and earn wages in the village. Apart from earning a wage, they also collect fuelwood, fodder for cattle as well as edible plants and animals from the wetlands or chaur area in both wet and dry seasons. Pila globosa or apple snail is one of the most consumed Mollusca among Musahar and Mallah communities. It is found in the paddy fields and wetlands in North Bihar in great numbers and cherished as one of the easily available sources of protein.

The communities living in the Kosi villages are mainly dependent on agriculture and fishing. When there is no work at agricultural fields, men from most of the lower caste communities including Musahar and Mallah, two of the most marginalized communities, out-migrate for labour work in other states of India and to Nepal for selling ice-cream on a bicycle. The women live in the villages throughout the year somehow managing the family with money sent by their husbands and sons, they also work in fields and earn wages in the village. Apart from earning a wage, they also collect fuelwood, fodder for cattle as well as edible plants and animals from the wetlands or chaur area in both wet and dry seasons. Pila globosa or apple snail is one of the most consumed Mollusca among Musahar and Mallah communities. It is found in the paddy fields and wetlands in North Bihar in great numbers and cherished as one of the easily available sources of protein.

While carrying out my in-depth semi-structured interviews with the Musahar community woman interviewee at Khainsa village of Kiratpur Block, Darbhanga district, North Bihar, I came across a term called ‘Hansuwa-farri’. The term translates to using a serrated sickle for earning a livelihood. Garima Devi Sada, while responding to a question about how do women manage life in the villages when their men are working in other states, she said, “Hamara sab ka ta ekai ta upay chhai-hansuwa–farri (sickle is our only and the last resort in our life, because we know nothing but to use hansuwa for earning wages, labour work is our only way out)”.

I got interested in the metaphor of hansuwa-farri and asked details from Garima Devi. She commenced her part that quickly unfolded into a nice account, a melange of their livelihood, their struggle, joy, and experience to manage the natural resource.

“See, babu, a serrated harvest sickle is a multifaceted tool in the hands of a woman. I can use it as a weapon against chauvinistic high caste males who so ever try to defile my dignity. There are instances when I heard of young married women from lower caste facing the situation of the male gaze and harassment from higher caste male. The serrated sickle on our shoulders deters such men from making any advance. Thus sickle is an integral part of our daily life in the rural Kosi villages. We use both for collecting fodder for the cattle and fuelwood for cooking apart using it for harvest.”

However, the use of serrated sickle for fishing apple Snail is far more interesting among Musahar and Mallah communities. She said, “The case of fishing for Apple Snail, a delicacy and one of the alternate sources of protein for us is very interesting. The Apple Snail or Ghongha as we call it in Maithili has very fleshy, chewy and juicy meat and therefore considered as a very good source of cheap protein”.

Most of the lower caste communities including Musahar and Mallah cherish fish as sources of protein in their diet, however not all could afford to buy fish, so people heavily rely on pulses for protein requirements. Rice and wheat are the staple sources of carbohydrates. The leafy shoots or climbing vegetables are grown at home gardens, such as bottle gourd, ash gourd, ridge gourds, pumpkin, ladies finger, potato, tomato, ginger garlic and brinjal etc, constitute the major portions of vegetable requirements. Besides, Colocasia (Colocasia indica), Tilkod (Coccinia grandis) and Karmi (Ipomoea aquatica) leaves are either collected from home garden, fringe areas or from the wetlands respectively. However, the lower caste communities do not have enough land for the home garden, so they heavily rely on the edible plant resources available outside on the common lands, such as wetlands. Coming to the apple snail, Garima Devi asserted that it also cleanses the gut.

She said, “The yellow fat reserves in Ghongha is far tastier than any meat and we enjoy is the most. The apple snail is very abundant in the rice fields and in the chaur (the shallow wetlands) area during monsoon. We, Musahar and Mallah, the fishermen community both cherish Ghongha dry fry along with fish and crabs during the summer monsoon.”

“However, both the abundance and demand for apple snail is short lived because once laid their eggs they start hiding deep into the bunds separating the agricultural fields for aestivation. On the other hand, post-egg laying season, apple snails tend to loose its fat reserves hence lack their usual taste. In fact, we wait for the apple snail to gain oil reserve and then go for fishing them in the post paddy harvest season in the month of December-January. It is during this time when we women set out to fishing Ghongha in the wetlands and along the bunds in paddy fields. We go in a group with serrated sickle hanging on our shoulders.”

She continued and narrated a very informative part of her story that showed how they rely on their traditional knowledge and experience to pull out apple snail from their refuge deep in the

soil. “From the years of experience and our traditional knowledge, we know that apple snails aestivate deep into the agricultural field bunds and in the areas adjoining to the wetlands and low lying paddy fields post monsoon. We use that understanding and its whereabouts while fishing for it in the group. The exact method of finding for apple snail is rather very simple. It goes like this – we poke the soil bunds with the tip of the serrated sickle. While poking the bunds with the tip of sickle when we hear the tong sound, it confirms the presence of apple snail in the bunds. Then we use the same sickle to dig out the precious catch. In a similar manner, we keep hitting the hard shell and take out the big Pila globosa, filled with fleshy fatty meat. Since we get it from the womb of the mother earth, we call it “Paatal Khassi” meaning lamb from the Paatal Lok or the Underworld.”

The metaphor of Paatal Khassi is so strong among the Musahar and Mallah communities is that they value it the most when it comes to meat. Eating some other kinds of meat is an acquired taste for them since the Musahar literally means one who eats rat and thus identify themselves as rat-eaters.  During paddy harvest, Musahars not only harvest paddy to earn a wage but dig out the field rats using deshi shovel called Kudaal, Hansuwa and Khudapi, a small tool made of iron to dig the soil. They catch the rat on request as well so that the landowners could get rid of the rats. The deal between Musahar and landowner is that Musahar would catch the rats and could take away the rats as well as paddy grains stored in the rat burrows in the agricultural fields as a reward. The Field rats caught in the due process are roasted on fire and mostly consumed in the field itself. Field rats are yet another example of meat from the Paatal Lok or the underworld.

During paddy harvest, Musahars not only harvest paddy to earn a wage but dig out the field rats using deshi shovel called Kudaal, Hansuwa and Khudapi, a small tool made of iron to dig the soil. They catch the rat on request as well so that the landowners could get rid of the rats. The deal between Musahar and landowner is that Musahar would catch the rats and could take away the rats as well as paddy grains stored in the rat burrows in the agricultural fields as a reward. The Field rats caught in the due process are roasted on fire and mostly consumed in the field itself. Field rats are yet another example of meat from the Paatal Lok or the underworld.

“We have folklore in this part of North Bihar that there are plenty of foods reserves hidden in the soil, one should know when and where to look for it. We also, dig out many edible tuberous roots, for example, Kadahad (root tubers of water lily), Sorkha (Root tuber of small lily), chichod (Sweet grass root) and Keshore (Wild Sweet root) found in the wetlands during post-monsoon when the water level is low. Identifying these plants and the time when one could harvest these fibrous roots is the key though. We mostly harvest them every year but historically our community has been harvesting these wild roots and fruits to survive through the time of drought and severe food scarcity. We also collect the juicy flowers of Mahuwa (Madhuca longifolia) tree and sundry it and grind it with rice flour to be used as a snack later on. We as well as our kids cherish black Jamun in the pre-monsoon season from the trees available all along the rivers and in the adjoining jungle area. We also collect bael (Aegle marmelos) during hot summer and make bael juice to relief ourselves from the heat of summer. With the erratic rain, most of the small rivers and the wetlands in North Bihar are drying though. So, they might lose these sources of seasonally available valuable wild fruits and roots.”

In fact, nowadays the wetlands rarely have water throughout the years and most of the low lying areas are also remaining dry, so getting all these wild fruits and roots are becoming more and more difficult. Also, with the availability of grains through PDS, the dependency on the wild fruits, tubers, and aquatic shoots and roots may have lessened but the nutritive value of wild food has not been replenished by PDS grains.

Nonetheless, the women still look for the aquatic fruits like water chestnut (Trapa natans), the fruit of water lily, Makhana (Euryale ferox) and collect them and use them as edibles for extra nutritional and medicinal values. If that also doesn’t work they have serrated sickle to support them and help them earn a living by harvesting both paddy and wheat, maize and pulses grown in the river floodplains of north Bihar. The Musahar community women believe that till they have serrated sickle in their efficient hands, they won’t starve to death anytime soon. It has been there for the older generations and will remain as an important tool for earning a wage and supporting their livelihood until someday all agricultural activities are automated and mechanized, which has happened elsewhere in Punjab and Haryana where wheat is harvested by big automated machines. But till then, men and women from Musahar, Mallah and other agricultural communities of north Bihar are hopeful that they would be able to earn a living through hansuwa-farri.

About Author: