Flowers are the reproductive organs of the flowering plants, they are flashy, can be extremely extravagant and roughly 352,000 flowering plant species (Angiosperms) make up about 90% of all living land plants. The morphological variation in the flowers has been a defining feature of the angiosperms from very early on in their evolution. Carl Linnaeus is often called the Father of Taxonomy used the variation in the sexual structure of flowers as the basis for the classification of plants. Unlike animals, the majority of sexually reproducing flowering plants (~352,000) are hermaphrodite (~90%), meaning both the reproductive structures present in the same flower of a plant (example, Tomato)1, and ~5% of plants have separate male and female flowers on the same individual plants are monoecious (example, Coconut tree)1. A minority of plant species is dioecious (i.e., having distinct male and female individual plants. For example papaya, bhang, and jathipathri). More than 15,000 dioecious species in angiosperm occurs in 987 genera (6%) and 175 families (38%)1. One of the key questions about the dioecious plants is its evolution, and animals eating the plants (herbivory) have been suggested as a pressure that resulted in the origin of separate male and female plants (dioecy)2. A number of ecological studies using a principle called ‘resource allocation’ has proven that there is a variation in distributing the available resource to defense, growth, and reproduction between male and female plants3. In general, a number of plant-herbivore interaction studies suggested a pattern of sex-biased herbivory in dioecious plants, i.e., herbivores prefer to graze male plants than female plants due to a significant variation in the composition of phytochemicals between the male and female plants. For example, a study on three palm trees (Chamaedorea Palms) reported that female plants leaves are tougher than male plants, and also the concentration of phenolic compounds are higher in female plants than male. As a result male plants were more susceptible to herbivory than female plants4. And also this study supports the general pattern that male plants grow taller than female plants, and invest less in defense whereas female plants spend its resource to defense and reproduction than vegetative growth4.

While ecological and phytochemical studies have showcased the variation in male and female plants, there are not that many studies to understand the medicinal properties of dioecious plants. India is one among the mega biodiversity countries, and rich in traditional knowledge on plants (i.e., Folk medicine, Ayurveda, Siddha), we planned a study to understand whether folk healers in India are aware of the existence of male and female plants? if they aware of different sexes of the plant do they have a preference to use any one gender to use for the purpose of medicine and/or food and timber?5 Also, does Ayurveda have any description about plant genders? If so, does Ayurveda prescribes a particular gender of the plant to be used medicinally?5. It was found that fruits being informed and considered as the main identity to distinguish male and female plants to the folk healers. It was observed that the visibility of fruit size, plant size, and few other characters determines the perception of a plant is male or female. For example, folk healers are unaware of the dioecy in shrubs where they use leaves for medicinal purpose, on the contrary healers have knowledge about the plants that do not produce seeds are considered to be male (Jyotishmati (Celastrus paniculatus), and Vai-vidanga (Emebelia tsjeriam-cottam)). Similarly, toddy prepared out of male palm trees is considered to be more potent than female plants. Likewise, the people have observed that the male trees produce less resin than female plants of Canarium stictum (Dhoop). Interestingly, folk healers have reported a gender preference for Piper betle (paan leaf) which are rather complex and dependent on spiritual believes and medication. When it comes to timber, people have a better understanding and preferring the plants that are taller, stronger and more durable, in such case, it was obviously male plants (example, Paanaai (Borassus flabellifer)). People preference on one gender in timber could be explained with plant resource allocation theory that the male plants comparatively allocate more resource to vegetative growth than the female plants. Apart from usages, the male plants are not considered as beneficial for other purposes. An example can be drawn from Papaya (Carica papaya) plant, where male members are very rare in the garden due to their inability to produce fruits5. Such selective logging and other anthropogenic activities that modify the male-female distance, sex ratio, plant size and pollinator abundance or behavior could affect the long-term viability of dioecious plants and leads to the risk of extinction of that particular member6.

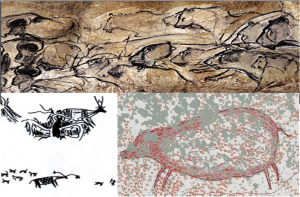

Apart from dioecious plants, people have their own cultural perceptions of naming a plant as male and female and use those plants with preference in different occasions. Classification and naming the plants according to the traditions broadly called Vernacular taxonomy. In such cases, folk healers also have a preference for choosing some plants as male and others as female which have apparently no biological basis. For examples, Clitoria ternatea (Shankapusphi) is attributed to gender in Kolli hills, Tamil Nadu. They consider white flower phenotype as female (resembles Indian female god Lakshmi) and blue flower phenotype as male (resembles Indian male god Krishna), and they prefer either one phenotype during the rituals and the choice of phenotype is based on the ritual process and whether the spiritual god is male or female. In this case, they just go by some characters of the plant to name the plants.

Our preliminary understanding on Ayurveda also suggests that Ayurveda has no indication on preferential usages towards genders of a plant but rather it has a description of the concept of reproductive morphology and sexual differentiation of plants (e.g. Kutaja: male plant (Pum-Kutaja- Holarrhena antidysenterica) and female plant (Stri-Kutaja- Wrightia tinctoria)). Ayurveda describes these two plants as male and female, but these two plants are not biologically male and female plants. Therefore, it appears that Ayurveda describes the plant genders on the basis of the appearance of fruits morphology of these two plants.

Unlike, Ayurveda and Siddha traditional knowledge, India also home to a vast diversity of ethnic people (Tribal people) and they have their own knowledge about medicinal plants and how to use it. This ethnomedicinal knowledge base is mostly verbal in nature and is orally transmitted through generations. Therefore, documentation of these practices and experiences is important to avoid complete loss of this knowledge base, and also there is a need to validate the claims or findings using the available scientific tools. For example, there is a popular belief although undocumented, that in Varanasi, leaves of the female cannabis plant are used to prepare ‘Bhang’, and they do not prefer to use male plant leaves7. Hence the question comes why only female leaves are preferred. So, we have to document this traditional practice first before it is lost, and then validate this practice via scientific tools, like analysis of chemical composition and variation in male and female plant leaves.

Many plant families such as Menispermaceae, Moraceae, Myristicaceae, and Putranjivaceae are entirely dioecious, and 5–7% of medicinal plants in Indian traditional medicines are dioecious plants5. However, there is a significant knowledge gap in the ethnobotanical literature on traditional knowledge of dioecious plants, particularly towards preferential gender usage. Therefore, based on our study we propose that researchers conducting ethnobotanical studies should consider documenting the traditional knowledge related to male and female plants. Documenting such knowledge could provide new ideas and strategies which can be applied in conservation biology, chemical ecology, ethnoecology and drug discovery.

References

- Renner, S. S. (2014). “The relative and absolute frequencies of angiosperm sexual systems: dioecy, monoecy, gynodioecy, and an updated online database.” American Journal of Botany 101(10): 1588-1596.

- Bawa, K. S. (1980). “Evolution of dioecy in flowering plants.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 11(1): 15-39.

- Obeso, J. R. (2002). “The costs of reproduction in plants.” New Phytologist 155(3): 321-348.

- Cepeda-Cornejo, V. and R. Dirzo (2010). “Sex-Related Differences in Reproductive Allocation, Growth, Defense and Herbivory in Three Dioecious Neotropical Palms.” PLoS ONE 5(3): e9824.

- Seethapathy, G. S., et al. (2018). “Ethnobotany of dioecious species: Traditional knowledge on dioecious plants in India.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 221: 56-64.

- Vamosi, J. C. and S. M. Vamosi (2005). “Present day risk of extinction may exacerbate the lower species richness of dioecious clades.” Diversity and Distributions 11(1): 25-32.

- Charukesi Ramadurai (2017). The cannabis plant’s role in Hindu mythology has authorities turning a blind eye to India’s drug shops. BBC. London, BBC.

*Author: Seethapathy G.S.

Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, School of Pharmacy, University of Oslo 0316 Oslo – Norway.

E-mail: g.s.seethapathy@farmasio.uio.no; seethapathygs@gmail.com