Human-animal interface manifests itself in several different ways, which may span anywhere in a gradient from conflict to cooperation. The interaction of humans with their nonhuman animal counterparts is as old as the emergence of Homo at the heart of Africa. Early humans needed to protect themselves, especially the vulnerable among them, from attacks by ferocious animals like lions or sabre-tooth tigers which roamed alongside humans in the vast savannas of Africa or the temperate meadows of Europe. The earlier human species, therefore devised various tools (especially spears) for such fights with large animals [1]. The hunter-gatherer lifestyle of early humans also required hunting a large number of different animals [2] ranging from small rodents to mammals as big as the wooly mammoth. Therefore, the influence of animals on early humans as predators (e.g. lions) or prey (e.g. aurochs) was arguably the greatest force behind necessitating humans to form groups or band together in a cooperative manner [3], which gradually evolved into what we call as “tribes”.

Animals occupied a great part of imagination in the prehistoric human societies, which often got expressed through totemism or art. The artifacts and signs left by early humans in the old stone-age period led us discover the earliest known form of art in the African as well as European archaeological sites. The middle to upper Paleolithic cave paintings and rock carvings by the earliest dispersed humans in Europe (e.g. France, Spain) have a recurring depiction of animals, which usually dominated their artistic creations. Drawings of predatory animals, description of a group hunting expedition, or a general portrayal of an interesting animal got done with great detail and accuracy, often using natural dyes like ochre or by simply using tools like axes or spears as etching instruments. As we can reasonably construe from archaeological evidence discovered so far, the occupation of animals on human imagination might have been the utmost influence in the beginning and development of human arts [4].

The prehistoric hunter-gatherers of central Asia found an unusual associate among wolves, some of which accompanied humans in their hunting expeditions as scavengers of left-over food from hunted animals. These wolves benefitted from human association as humans tolerated them because they possibly helped humans in hunts as well as guarded humans or acted as early warning system from potential dangers. The mutualism between wolves and early human hunter-gatherers later evolved into the first domesticated wolves, or dogs, in central Asia [5] during the last part of the Paleolithic period (although strong arguments exist in support of an European origin of domestic dogs [6]). Later on, sheep and goats were domesticated for meat production as well as valuable sources for milk and wool. Cattle were domesticated in the later period in two separate regions, the modern day Turkey (from aurochs) and Pakistan (from wild cattle, possibly Gaur or Indian bison), first for meat and later as an important source of milk. These early domestications of wild animals for human utilization heralded a new period in human history, the Neolithic period or the New Stone Age. The early Neolithic humans also domesticated certain wild plants from which they gathered food regularly, which led to the origin of early agriculture. The increased dependence of Neolithic humans on domesticated animals and plants for food and other commodities required them to make semi-permanent settlements which later became permanent villages and led to the final stages of cultural evolution among prehistoric humans, including the making of advanced stone tools, pottery, weaving and agricultural revolution [7] (with the use of draught animals and agricultural tools). By the onset of the Bronze Age, humans had practically become dependent on domestic animals for food, commodities (wool, hide, horns etc.), agriculture, transportation or other draught-works.

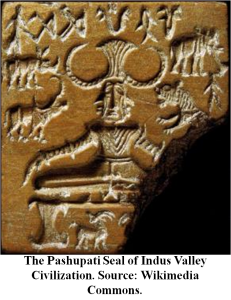

The importance of domestic animals in Neolithic, Bronze Age and the later Iron Age period led to an increased depiction of animals in totemism and greatly influenced the development of organized religion. Thus a new aspect of human-animal interface began to develop, i.e., spiritual reverence of animals. Early human civilizations from every corner of the world, be it the old world or the new world, had animals at the centre of their religious beliefs. For example, the Egyptians revered various holy animals like the baboon, the jackal, the cat etc., and the Indus Valley people depicted a godly figure who was the lord of the animals (the Pashupati seal of Mohenjo-daro having various animals including a rhinoceros, a water buffalo, an elephant, and a tiger) [8].

period led to an increased depiction of animals in totemism and greatly influenced the development of organized religion. Thus a new aspect of human-animal interface began to develop, i.e., spiritual reverence of animals. Early human civilizations from every corner of the world, be it the old world or the new world, had animals at the centre of their religious beliefs. For example, the Egyptians revered various holy animals like the baboon, the jackal, the cat etc., and the Indus Valley people depicted a godly figure who was the lord of the animals (the Pashupati seal of Mohenjo-daro having various animals including a rhinoceros, a water buffalo, an elephant, and a tiger) [8].

The development of religious importance of animals also possibly led to the earliest form of protection to certain wild animals as well as their habitats. The significance of animals may also have greatly influenced the aesthetic appreciation and the representation of animals in arts, literature, and scientific investigation.

In the modern human society, animals occupy a much greater space than ever before. The industrial revolution and the subsequent invent of technology in every aspect of human life have made the human species to rapidly expand in numbers as well as made them to occupy newer territories. These, combined with a rampant exploitation of natural resources, have inevitably decreased the space for wild animals leading to the extinction of a number of species and the endangering of the much of the rest. Human development in the current age mostly requires encroachment upon wild lands, which leads to human-wildlife conflicts. Some of these encroachment related conflicts can be deadly to animals, like the deaths of elephants crossing railway lines. These conflicts can also lead to economic loss, like the crop-depredation by wild herbivores due to agricultural expansion and the destruction of wild habitats of animals causing a shortage of food for them. Conflicts give rise to animosities. The negative attitude of humans towards conflict animals combined with an ever increasing alienation of the modern society from nature and wildlife give rise to situations where animals are actively injured or killed by people. One recent example of this animosity leading to the death of the animal can be the case of Lalgarh Tiger. The unusual tiger in a human dominated secondary natural habitat made the local people as well as the outsiders afraid, angry and repelled by the animal. The collective negative attitude towards the tiger ultimately led to its death [9]. This happened in the guise of an obscure and vastly condemnable practice of so-called tribal cultural hunting festival [10], which should not have any existence in the modern times. The practice causes the death of thousands of animals every year, rare and common alike, in the name of preserving the tradition of local tribes.

have inevitably decreased the space for wild animals leading to the extinction of a number of species and the endangering of the much of the rest. Human development in the current age mostly requires encroachment upon wild lands, which leads to human-wildlife conflicts. Some of these encroachment related conflicts can be deadly to animals, like the deaths of elephants crossing railway lines. These conflicts can also lead to economic loss, like the crop-depredation by wild herbivores due to agricultural expansion and the destruction of wild habitats of animals causing a shortage of food for them. Conflicts give rise to animosities. The negative attitude of humans towards conflict animals combined with an ever increasing alienation of the modern society from nature and wildlife give rise to situations where animals are actively injured or killed by people. One recent example of this animosity leading to the death of the animal can be the case of Lalgarh Tiger. The unusual tiger in a human dominated secondary natural habitat made the local people as well as the outsiders afraid, angry and repelled by the animal. The collective negative attitude towards the tiger ultimately led to its death [9]. This happened in the guise of an obscure and vastly condemnable practice of so-called tribal cultural hunting festival [10], which should not have any existence in the modern times. The practice causes the death of thousands of animals every year, rare and common alike, in the name of preserving the tradition of local tribes.

Although the situation is indeed worrisome and the future of wild animals in the modern world is bleak, all is not bad news. The interface of humans and animals is as old as the humanity itself, and a vast majority of people still positively associate with animals. Various initiatives by the government, the NGOs, the scientists as well as the common people have been actively implemented towards conservation of wildlife and natural habitats. Most of us have understood the simple fact that human species is not different from the rest of the lives on earth and we cannot survive outside the natural world. Thus, the preservation of the delicate balance of nature, on which humans and animals are equally dependent through unbreakable associations, could be the only way towards a sustainable world.

Reference

1. Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S., Noack, E. S., Pop, E., Herbst, C., Pfleging, J., Buchli, J., … Roebroeks, W. (2018). Evidence for close-range hunting by last interglacial Neanderthals. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2018, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41559-018-0596-1

2. Domı́nguez-Rodrigo, M. (2002). Hunting and scavenging by early humans: the state of the debate. Journal of World Prehistory, 16(1), 1–54.

3. Robin McKie. (2012). Humans hunted for meat 2 million years ago. Retrieved July 1, 2018, from https://www.theguardian.com/science/2012/sep/23/human-hunting-evolution-2million-years

4. Morriss-Kay, G. M. (2010). The evolution of human artistic creativity. Journal of Anatomy, 216(2), 158–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01160.x

5. MacHugh, D. E., Larson, G., & Orlando, L. (2017). Taming the Past: Ancient DNA and the Study of Animal Domestication. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, 5(1), 329–351. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-022516-022747

6. Botigué, L. R., Song, S., Scheu, A., Gopalan, S., Pendleton, A. L., Oetjens, M., … Veeramah, K. R. (2017). Ancient European dog genomes reveal continuity since the Early Neolithic. Nature Communications, 8, 16082. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms16082

7. Martin, K., & Sauerborn, J. (2013). Origin and Development of Agriculture. In Agroecology (pp. 9–48). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5917-6_2

8. Marshall, J. (1931). Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus civilization: being an official account of archaeological excavations at Mohenjo-Daro carried out by the Government of India between the years 1922 and 1927. Asian Educational Services.

9. Raza Kazmi. (2018). We know how the “Lalgarh tiger” died. But where did it live? Retrieved July 1, 2018, from https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/we-know-how-the-lalgarh-tiger-died-but-where-did-it-live/article23773313.ece

10. Phadikar, A., & Mitra, D. (2018). Hunters kill Lalgarh tiger. Retrieved July 1, 2018, from https://www.telegraphindia.com/calcutta/hunters-kill-lalgarh-tigergroup-throws-arrows-spears-223350