Sarika1, Anusha Chaudhary2, Anuradha Kumari1 and Bharti Chandel1

1- Research Scholar, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

2- Researcher, Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University, New Delhi

E-mail: sarika40_ses@jnu.ac.in, anusha.chaudhary98@gmail.com, anupandey304@gmail.com, chandelb24@gmail.com

“Cultural diversity is necessary for humankind as biodiversity is for nature.”

-UNESCO Declaration, 2001

Development, defined in terms of western concepts of societal interactions, had a significant impact on radically altering the existing institutional structures among mountainous villages (Berreman et.al., 1963). The Himalayan region is home to one of the world’s most dynamic and complex mountain systems. Uncertainties concerning the rate and extent of climate change with possible consequences abound, but there is no denying that climate change is altering the Himalayan region’s natural and socioeconomic landscape (Eriksson et.al.,2009). Inhabitants of the Himalayas manifest their unique ethno-cultural traits, socio-cultural heritage, lifestyle, and customs as it is home to several amalgams of tribes with diverse backgrounds and their close interaction with the environment. The local communities and indigenous people are important stewards for the biodiversity and natural environment of the Himalayan ecosystem. These communities help to shape the environment through their customs, lifestyle, and livelihood practices. The social structure and traditional economic activities signify various innovative ways coupled with management techniques adapted for the region’s limited resources. The Himalayan Mountains are famous for traditionalism with a conservative social values along with inaccessibility, remoteness, and relatively stable utilization practices, which often kept them away from external influences (Beniston et.al.,2003). Modernization has dramatically transformed the high altitude inhabitants’ social structures, nurturing many present-day problems for e.g.: change in pattern of sedentary activities (gathering fodder and fuelwood, managing herds, farming etc.,), agricultural practices, traditional crafts and art forms (wood carving, Bamboo sculpture, silver and gold jewellery, shawls, carpets and rugs weaving etc.) (Satyal et.al.,2017; Aayog et.al.,2018). The process of social transformations has had a consequent and drastic effect on the Himalayan heterogeneity. This includes physical, ecological, social, and cultural aspects. Population relies on the delicate inelastic physical environment for their subsistence. Besides this, they also need to create additional surpluses such as food products, organic commodities, and capital to maintain incoming popular demands (Ives et.al.,2012). This type of consumerist culture influences the plethora of communities and tribes, which has changed the human-environment equipoise. It has occurred due to replacement of the traditional attire, animal husbandry, cash-cropping and horticulture practices, and ornaments, with modern apparels and products (Thompson et.al.,2007). These issues are as delicate as the physical environment. Unfortunately, the development process, inclusive of Environmental Impact Assessment, overlooks the social and cultural consequences of any large scale project. Thus, neither the project developers nor the government values the objections of local residents regarding marginalisation or the necessity to conserve areas for religious and spiritual beliefs (Ives et.al.,2019). The conspicuous increase in the commercial exploitation of mountain-based resources has served as raw materials for a broad spectrum of commodities, the use of which is a status symbol and demonstrates a luxurious lifestyle that has had many drastic impacts and surged unsustainability. Subsequently, it has led to extensive deforestation, unsustainable harvest of medicinal plants, and ecosystem destruction due to extraction of minerals. In the era of road infrastructure developments, air links and digitalization impact the communities’ socio-economic condition.

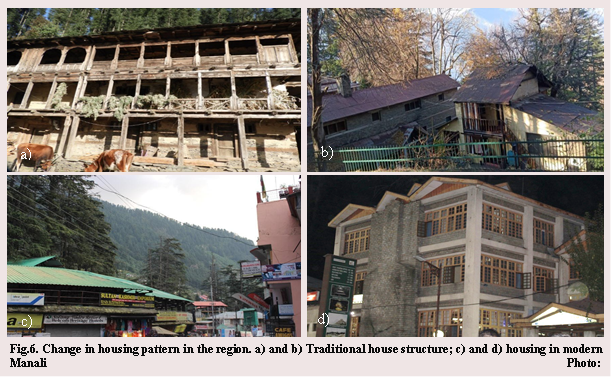

We have illustrated these transformations using a case study of the Himalayan town of Manali based on observation from our social survey. Manali’s vegetation and quietness have been drawing in tourists since provincial times. It has now evolved into areas that are no longer isolated or less developed and people are exposed to new opportunities to obtain income outside their traditional systems. Recent development and market facilities have provided new opportunities to increase income through different practices such as lending houses on a lease, replacing traditional houses with luxurious concrete buildings, and converting forest and cropland into lavish resorts and tourist spots. This hill station appears modest, but as one begins the journey as a tourist, the absence of waste disposal, endless chains of hotels and homestays, overcrowded lanes and commercialism become more evident.

Is Tourism healthy for traditional culture?

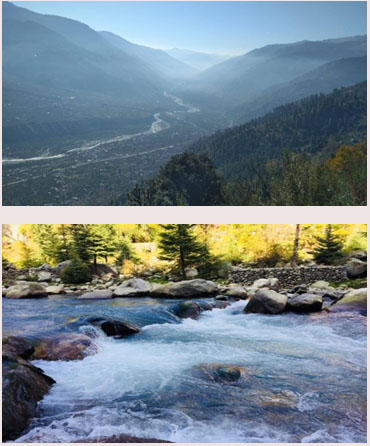

Manali is a small town nestled in the mountains of Himachal Pradesh, India located close to the northern end of the Kullu Valley at an elevation of 2,050 m (6,726 ft) in the Beas River valley. This town has a population of 8,096. It is one of India’s most popular tourist destinations and serves as the gateway to Leh, Lahaul, and Spiti districts. It beholds a wide variety of biodiversity including forests comprising of deodar (Cedrus deodara), walnut (Juglans regia), horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum); animals like Himalayan Monal (Lophophorus impejanus), Western Tragopan (Tragopan melanocephalus), Kashmiri Flying Squirrel (Eoglaucomys fimbriatus), Himalayan Black Bear (Ursus thibetanus laniger), Himalayan Yellow-Throated Marten (Martes flavigula), Flying Fox (Pteropus vampyrus), etc. With an inundation of migrants from around the world, Manali has broadened and adjusted within its current population.

The mountain environment offers substantial economic opportunities to the community, which attracts stakeholders to invest in mountain-based economic activities such as hydropower generation, mining industries, infrastructure constructions, etc., resulting in a colossal loss of the ecosystem with the entire resource base. However, traditional occupational practices are associated with vertical and horizontal space amongst population and animals concerning time, space, and communal control, reflecting indigenous people’s cultural ecology and sensitivity towards nature (Tiwari et.al.,2015). Regarding the status of indigenous peoples, once the former Prime Minister Pt. Nehru expressed fears about “how anxious people are to shape others in their own image or likeness, and to impose on them their particular way of life.” The Himalayan system is responding sensitively and illustrates feedback related to both climatic and non-climatic stressors. Traditionally, inhabitants’ livelihood practices include land cultivation, raising livestock (yaks, goats, sheep, cows are kept for milk, wool, and meat products), cottage manufacture and ethnic commodities production, etc. These practices are based on a barter system with few monetary transactions (Everard et.al.,2019). All such practices have undergone fundamental changes, which has led to a decrease in local self-reliance. Consequently, their impact has created analogous changes in the society and environment, which may vary from area to area.

Traditional social milieu is a significant constituent of the current social and ecological scenario as traditional knowledge and practices are imperative in judicious resource use and biodiversity conservation. Moreover, it is very challenging to cease and understand the ecological deterioration devoid of social transformation knowledge despite being an essential and immediate concern. Buddhism has a strong influence on the population due to the high number of migrants from Lahaul, Spiti and Ladakh. Many people worship the Goddess Hadimba, often referred to as the reincarnation of Goddess Kali by the locals.

She is perceived as a protector from chaos, a harbinger of peace, and to ensure the safety of the entire town (Fig. 2). Many localities suggested that there are approx. 18 types of animal sacrifices offered in the Hadimba Temple occasionally, but surprisingly, only the elderly were able to recall a few of the folk stories regarding the beliefs associated with them. These stories have been passed on over generations verbally with moral significance. We opine that folk tales should be documented and mentioned in children’s stories, books and literature etc. to promote regional knowledge. It will help in building a strong connection with culture among young minds.

She is perceived as a protector from chaos, a harbinger of peace, and to ensure the safety of the entire town (Fig. 2). Many localities suggested that there are approx. 18 types of animal sacrifices offered in the Hadimba Temple occasionally, but surprisingly, only the elderly were able to recall a few of the folk stories regarding the beliefs associated with them. These stories have been passed on over generations verbally with moral significance. We opine that folk tales should be documented and mentioned in children’s stories, books and literature etc. to promote regional knowledge. It will help in building a strong connection with culture among young minds.

The temple surroundings remain encumbered by sellers most of the time. Religious tourism is one of the major sources of earnings for the local people as many festivals take place there annually, bringing a large incursion of tourists during these times. Each festival (Mela) is celebrated with a specific fair that occurs during a particular time, for example, Fagdi Mela occurs between April and May, Nagdevta Mela occurs  during the rainy season followed by Shakh Mela and Sheri Mela (Fig.3). The number of visitors increases during that time, therefore, the heightened market demand and supply of religious artifacts like feathers,

during the rainy season followed by Shakh Mela and Sheri Mela (Fig.3). The number of visitors increases during that time, therefore, the heightened market demand and supply of religious artifacts like feathers,

Rudraksha ornaments, idols of deities, flowers for deities, food items, local medicinal herbs, etc. Rudraksha is the drupes of the Elaeocarpus ganitrus (large broad-leaved evergreen tree).

Rudraksha is rudrākṣa, which means “Rudra’s teardrops” or “eyes” in sanskrit. It is popularly

used as prayer beads and in the creation of malas (garlands) (Koul et.al.,2015). Vendors were selling Shilajit, Kesar and various different dry fruits. photographs with Angora rabbits to yaks for rides, the area around the temple appeared more of a market than a shrine. Shilajit and Cannabis were among the popular items marketed discreetly. However, as per the locals, the real Shilajit is not found in Manali. Its whereabouts fluctuate between Old Manali, Ladakh and Jammu & Kashmir.

Shilajit, commonly named as salajit, shilajatu, mimie, or mummiyo, is a blackish-brown powder or exudate found in high mountain rocks, particularly in the Himalayan mountains (Srivastava et.al.,2010). According to researchers, Shilajit is a natural phytocomplex produced by the decomposition of plant material from species including Euphorbia royleana and Trifolium repens (Carrasco-Gallardo et.al.,2012). Shilajit is well-known for its ayurvedic properties. It is believed to provide many health benefits such as increased longevity, prevention from high altitude sickness, rejuvenation, fertility and anti-aging effects etc. Shilajit’s health benefits have been observed to vary based on where it was extracted (Agarwal et.al.,2007). Saffron is a spice made from the Crocus sativus flower. It is a widely cultivated perennial stemless herb (Srivastava et.al.,1985). The dried crimson stigma and a little amount of the yellowish style are used to make commercial saffron. It has long been an essential ingredient in the recipes of our forefathers in the field of Indian medicine, and its cultivation is in Jammu and Kashmir exclusivity (Srivastava et.al.,2010) (Fig.4).

Influx of migrants have somewhat dissolved pre-existing casteism. This has positively affected the public in general and has expanded the attitude towards business networking and companionship. Among the natives, which hold less than ten percent of the population, three languages are broadly spoken – Pahadi, Lohali, and Kinnauri. There are around five types of dialects spoken in Kullu. Changes in the local language can be observed as one travels up the mountain. Multilingualism in the Himalayas has also contributed to the extinction of several Himalayan languages (Luger & Höivik). The liturgical languages (Sanskrit and Tibetan) tend to remain, albeit mostly as a script, while more prominent languages from neighbouring places are adopted for daily usage. Linguistic diversity has had an impact on customs and rituals. They use different leaves as incense and the

wood of various trees during their customary religious practices. Documentation, publication, and dissemination are utilised in a variety of ways to conserve and maintain the use of these cultural forms. Corroboration and preservation of endangered language dictionaries, traditional pharmacopoeia, and music and dance recordings are a few examples. However, there is an extensive scope for rigorous study to capture lingual diversity.

Over the years, the contemporary lifestyle and economic reforms have dwindled traditional knowledge and sustainable practices and enhanced the economic status, availability of market products, and the cash flow of the communities. These developments often come at the cost of the environment. The luxurious lifestyle demonstrating modernization has influenced the majority of the population as it signifies possession of wealthy status. There are ample examples that show social transformations in the Himalayas, such as a decline in the use of wild resources by indigenous people or their use restricted only for which no cheap source is available in the market. However, elderly women still prefer to wear handwoven dresses like Pattu, including a belt called Sultan. It is worn along with an overcoat called Chota, Dhattu, and Tarmaania along with traditional ornaments. Large shawls called Chaddar and Pashmina made out of cashmere wool and the Kashmiri, Angoori and Laholi varieties are the most popular among the tourists. The Topi, a circular cap, is widely worn by men in this area. For specific occasions like weddings or festivities, each Topi is beautified with feathers of regional body. Adding feathers to the cap is believed to be a symbol of happiness and prosperity (Fig.5).

Manali offers a wide variety of foods from various cultures including Indian cuisine from all the parts of the nation to international cuisines like Thai, Lebanese and Chinese. Regional food items include Shiddu- steamed wheat bread stuffed with spicy walnut paste, Aksru- made out of ground rice, Katthu, Siryara, red rice, etc are also available (Naudiyal et.al.,2019). Raw spices include wild cumin like Morchella conica (Gucchi wild mushrooms) and Farna (Singh et.al.,2016) are harvested from the forest regularly and are incorporated in a variety of local dishes. However, the

Manali offers a wide variety of foods from various cultures including Indian cuisine from all the parts of the nation to international cuisines like Thai, Lebanese and Chinese. Regional food items include Shiddu- steamed wheat bread stuffed with spicy walnut paste, Aksru- made out of ground rice, Katthu, Siryara, red rice, etc are also available (Naudiyal et.al.,2019). Raw spices include wild cumin like Morchella conica (Gucchi wild mushrooms) and Farna (Singh et.al.,2016) are harvested from the forest regularly and are incorporated in a variety of local dishes. However, the

demand for fast food has overshadowed regional customary dishes. If the invasion of foreign cuisines continues at this pace, the traditional food items that highlight the uniqueness of Manali will disappear soon. However, the concept to preserve cultural cuisine has gained traction, particularly in the context of the increasing need to explore foods which have more nutritional value. Inclusion of regional dishes in menus would give the needed exposure as well as provide nutritious alternate food options.

Nonetheless, tourism has impacted almost every aspect of this town. The dependency on high-value market products and deterioration in the traditional knowledge, gained through experiences of thousands of years, for short-term economics is beneficial but not sustainable in the long run. The cultivation of cash crops (such as potato, French beans, pea, apple, fig, etc.) instead of indigenous variety and migration of the local population to other areas due to decreased agricultural productivity and better livelihood opportunities by lending their land on lease for commercial purposes (Ives et.al.,2003). Collectively these activities

indicate social and economic development of communities, on the contrary, it has led to the loss of various wild varieties of crops and environmental deterioration. These wild varieties play a crucial role in maintaining biodiversity as many regional birds and insect species depend on them for food and shelter. Therefore, equating development with destructive impacts on the ecosystem and socio-economic systems is not justified. It is a matter of striking a balance between environmental sustainability and economic development. Though changed community lifestyle and market economy both influence each other in many aspects, one such example is replacing Rumexnepalensis (Jungli Palak), a traditional dye plant, with chemical dyes used to color woolens (Singh et.al.,2016). Similarly, animal feed like leaf fodder, etc., was available from the surrounding forest instead of purchasing from the market.

indicate social and economic development of communities, on the contrary, it has led to the loss of various wild varieties of crops and environmental deterioration. These wild varieties play a crucial role in maintaining biodiversity as many regional birds and insect species depend on them for food and shelter. Therefore, equating development with destructive impacts on the ecosystem and socio-economic systems is not justified. It is a matter of striking a balance between environmental sustainability and economic development. Though changed community lifestyle and market economy both influence each other in many aspects, one such example is replacing Rumexnepalensis (Jungli Palak), a traditional dye plant, with chemical dyes used to color woolens (Singh et.al.,2016). Similarly, animal feed like leaf fodder, etc., was available from the surrounding forest instead of purchasing from the market.

Elderly people believe that western culture has impacted the younger generation and disconnected youth from their ancestral roots. Many people have moved to cities from their villages for minor businesses and better job opportunities. Whereas, forests have been converted into picnic spots and trekking trails which has led to unsolicited anthropogenic activities in forests. Liquor bottles, plastic trash, leftover food items and half-burnt wooden logs can be seen within every few meters, even at the top of the hills. Current social media trends have aggrandized the aforementioned activities in the name of “close-to-nature” tourism. Rapid conversion of forest patches into urban structures for resorts and homestays has increased over time (Fig.6). This has led to forest fragmentation and habitat degradation of various floral and faunal species found in the region.

Conclusion

The incursion of tourists poses a threat to the culture and biodiversity of this quaint Himalayan town. The extent of many cultural forms (language, arts & crafts) to younger generations are not followed and are unable to evolve with modern lifestyles & needs. Hence, it has led to declination of traditional systems and change in values and behaviors of youth towards the environment. Manali has been hit by a rapid invasion of foreign cultures, a subsequent loss of linguistic diversity and snowballing rates of urbanization. However, sensitization and building awareness among tourists and locals alike can mitigate the damage that has taken place so far. This awareness must be encouraged in the indigenous communities, enabling them to flourish via educated decision, bolstered by a belief and pride in their own heritage, as well as an understanding and compassion for innovation. We should try to optimally practice the traditional sustainable way of life to conserve our biodiversity in the era of climate crisis. Government should promote holistic village tourism as well as eco-tourism but without hampering cultural diversity so that people gain valuable information, experience their lifestyle and comprehend cultural heritage. The knowledge regarding regional endemic flora and fauna should be considered during policy making and proposed developmental projects in Himalayan region. Nevertheless, there is a wide scope to record details and association of ethnic diversity with biodiversity which would help in making informed and culturally sensitive decisions along with their development.

References:

- Aayog, N. (2018). Report of Working Group II: Sustainable Tourism in the Indian Himalayan Region. New Delhi.

- Agarwal, S. P., Khanna, R., Karmarkar, R., Anwer, M. K., & Khar, R. K. (2007). Shilajit: a review. Phytotherapy Research: An International Journal Devoted to Pharmacological and Toxicological Evaluation of Natural Product Derivatives, 21(5), 401-405.

- Banerji, G., & Fareedi, M. (2009). Protection of cultural diversity in the Himalayas. In I n A background paper for a workshop on addressing regional disparities: Inclusive & culturally attuned development for the Himalayas, New Delhi.

- Beniston, M. (2003). Climatic change in mountain regions: a review of possible impacts. Climate variability and change in high elevation regions: Past, present & future, 5-31.

- Berreman, G. D. (1963). Peoples and Cultures of the Himalayas. Asian Survey, 289-304.

- Carrasco-Gallardo, C., Guzmán, L., & Maccioni, R. B. (2012). Shilajit: a natural phytocomplex with potential procognitive activity. International Journal of Alzheimer’s disease, 2012.

- Eriksson, M., Xu, J., Shrestha, A. B., Vaidya, R. A., Nepal, S., & Sandstram, K. (2009). Impact of climate change on water resources and livelihoods in the greater Himalayas. The Changing Himalayas, 1-26.

- Everard, M., Gupta, N., Scott, C. A., Tiwari, P. C., Joshi, B., Kataria, G., & Kumar, S. (2019). Assessing livelihood-ecosystem interdependencies and natural resource governance in Indian villages in the Middle Himalayas. Regional Environmental Change, 19(1), 165-177.

- Goldstein, M. C. (1981). High-altitude Tibetan populations in the remote Himalaya: social transformation and its demographic, economic, and ecological consequences. Mountain Research and Development, 5-18.

- Ives, J. D. (2012). Environmental change and challenge in the Himalaya. A historical perspective.

- Ives, J. D. (2019). Development in the Face of Uncertainty (1). In Deforestation (pp. 54-74). Routledge.

- Ives, J. D., & Messerli, B. (2003). The Himalayan dilemma: reconciling development and conservation. Routledge.

- Koul, M. K. (2001-05-13). “Bond with the beads”. Spectrum. India: The Tribune.

- Luger, K., & Höivik, S. With Reverence for Culture and Nature: Development and Modernization in the Himalaya Mit Ehrfurcht vor Kultur und Natur: Entwicklung und Modernisierung im Himalaya. na.

- Naudiyal, N., Arunachalam, K., & Kumar, U. (2019). The future of mountain agriculture amidst continual farm-exit, livelihood diversification and outmigration in the Central Himalayan villages. Journal of Mountain Science, 16(4).

- Satyal, P., Shrestha, K., Ojha, H., Vira, B., & Adhikari, J. (2017). A new Himalayan crisis? Exploring transformative resilience pathways. Environmental Development, 23, 47-56