The Mallanimli Baobab of Orchha, India, the great Banyan tree of Kolkata Botanical Garden, the giant red woods of California, the ancient Ginkgos in China, the mighty dipterocarps in Malaysia or the eucalypts piercing the Australian landscapes, all these trees keep mesmerizing us not just by their larger than life presence, but also by their ancient links with our forefathers. These widely known woody giants not only instigate our romanticism about nature, but they also remind us about the past features of the landscape and peoples’ affection towards it. Historically, ancient trees in many areas are symbolic of socio-religious links humans had with nature. They are present in the forest, pasture, rangeland, valleys and agriculture lands reflecting local land use decision, and cultural profile of the communities. But, how to define ancient or old trees? There is no universal definition for ancient trees except few visual clues. They can be characterized by their wider trunks (compared with other individuals of the same species), and low, fat and squat shape; however, it could be specific to species, site and environmental conditions (www.ancienttreeforum.co.uk). Their presence in diverse ecosystems across tropics and temperate indicate wider tolerance to environmental changes and acceptance to a large number of communities.

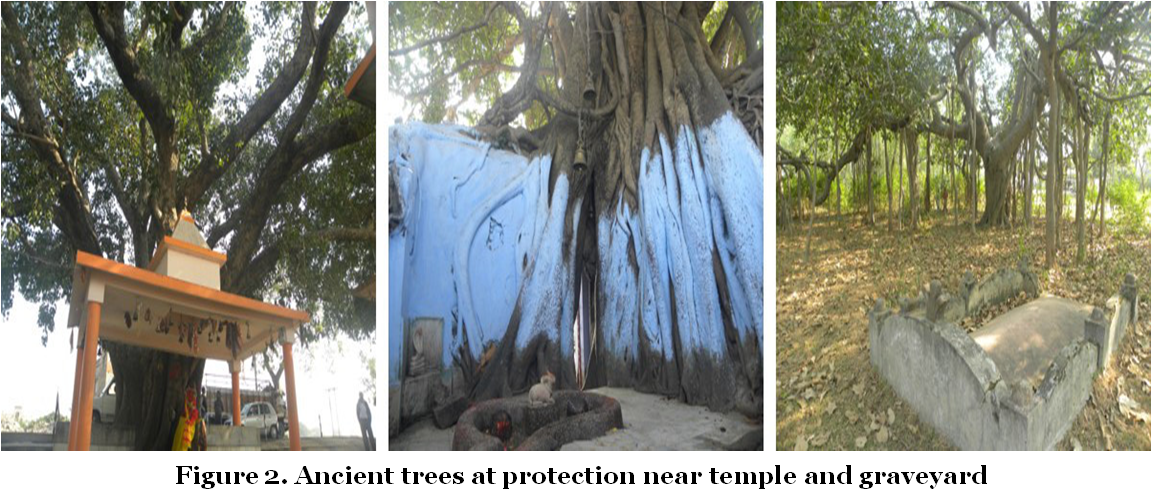

In India, scores of old growth trees are highly venerated in cultural and religious practices as evidenced in anecdotal resources. Moreover, their association with mythological stories, historical events, and social activities are widely covered in the literature. The celebrated examples are Ficus spp. (Ficus religiosa (pipal), Ficus benghalensis (banyan)), Mangifera indica (mango), Tamarindus indica (tamarind), Shorea robusta (sal) (Upadhyaya 1964, Gupta 2001) (Figure 1). Their antiquity mostly felt in religious institutions and sacred natural sites where they are an integral part of the religious architecture irrespective of diversities of faith. There are Stalavrikshas in temples of Tamilnadu, Sai Baba Neem in Shirdi, Maharashtra, Panchavati in Nasik, Maharashtra, great banyan tree at Natna, West Bengal, Pipal tree at Jain Dilwara temple, Mt. Abu, Rajasthan, Mulberry tree at Joshimath, Uttarakhand and countless other members occupy our religious landscape. Sometimes, these trees are places of worship or older than the formalized worshipping places. Graveyards and cemeteries in India also have their own component of tree vegetation too where due to various taboos disturbance is less and our green grandparents can survive (Mango trees in Park St. Cemetery, Kolkata, Chinsurah Dutch cemetery, West Bengal). Remember our childhood ghost stories. Old spreading banyan trees with their spreading branches, hanging aerial roots, and dense foliage, were favourable adobe for our rural area ghosts. Those entangled branches with sparkling fireflies and roaming bats at dark night were scary enough for any lone passerby. The daytimes presented more of a pleasant picture of such trees, in singles or clusters, may be ficus or neem, mahua or mango, Alstonia or bakula in serene landscapes, often nearby village ponds. Cumulatively these practices or beliefs act as a protective shield for old trees (Figure 2).

social activities are widely covered in the literature. The celebrated examples are Ficus spp. (Ficus religiosa (pipal), Ficus benghalensis (banyan)), Mangifera indica (mango), Tamarindus indica (tamarind), Shorea robusta (sal) (Upadhyaya 1964, Gupta 2001) (Figure 1). Their antiquity mostly felt in religious institutions and sacred natural sites where they are an integral part of the religious architecture irrespective of diversities of faith. There are Stalavrikshas in temples of Tamilnadu, Sai Baba Neem in Shirdi, Maharashtra, Panchavati in Nasik, Maharashtra, great banyan tree at Natna, West Bengal, Pipal tree at Jain Dilwara temple, Mt. Abu, Rajasthan, Mulberry tree at Joshimath, Uttarakhand and countless other members occupy our religious landscape. Sometimes, these trees are places of worship or older than the formalized worshipping places. Graveyards and cemeteries in India also have their own component of tree vegetation too where due to various taboos disturbance is less and our green grandparents can survive (Mango trees in Park St. Cemetery, Kolkata, Chinsurah Dutch cemetery, West Bengal). Remember our childhood ghost stories. Old spreading banyan trees with their spreading branches, hanging aerial roots, and dense foliage, were favourable adobe for our rural area ghosts. Those entangled branches with sparkling fireflies and roaming bats at dark night were scary enough for any lone passerby. The daytimes presented more of a pleasant picture of such trees, in singles or clusters, may be ficus or neem, mahua or mango, Alstonia or bakula in serene landscapes, often nearby village ponds. Cumulatively these practices or beliefs act as a protective shield for old trees (Figure 2).

Leaving apart the literature, many of us would fondly recall the existence of old banyan/pipal/neem/mango trees in our surroundings which were not only our favourite playground but also a remarkable landmark for multiple purposes for all walks of people. Examples can be drawn from our daily life, a landmark for someone’s house or associated with places of our daily amenities like laundry, tailor, grocery shop, the fruit seller, bus stop, local market place etc. it may be a place where locals get together in evenings or rendering cool shade in scorching summer for humans and cattle. Except for places with religious and social importance, often they are found in private property as a symbol of family’s proud possession through generations, or in not so easily accessible areas like mountainous terrain. With the passage of time, many of them received the heat of development in the name of city expansion, road widening, power line or dam construction and wiped away from our landscape.

but also a remarkable landmark for multiple purposes for all walks of people. Examples can be drawn from our daily life, a landmark for someone’s house or associated with places of our daily amenities like laundry, tailor, grocery shop, the fruit seller, bus stop, local market place etc. it may be a place where locals get together in evenings or rendering cool shade in scorching summer for humans and cattle. Except for places with religious and social importance, often they are found in private property as a symbol of family’s proud possession through generations, or in not so easily accessible areas like mountainous terrain. With the passage of time, many of them received the heat of development in the name of city expansion, road widening, power line or dam construction and wiped away from our landscape.

The common notion about rural landscape with its greenery studded with magnificent heritage trees, seems to be a feature of past in the near future. It is due to modernization of agriculture and rapid socio-economic changes we are losing our rural plant diversity which is often replaced by economically important species be it timber or cash crops. A pertinent example can be cited from road network establishment program. Aimed at greater connectivity and economic prosperity of even interior villages, the implementations are ecologically and environmentally insensitive in most places of India. Large numbers of good old trees are cut without giving a second thought and as compensation, we are getting Acacia, Eucalyptus, Casuarina, Peltophorum spp. For rural folk, these trees are financially acceptable as they grow fast, people are getting money for their maintenance and even for cutting and selling (Figure 3). On the flip side, nobody concerns about the soil quality deterioration, disruption in nutrient cycling, adverse impact on local fauna. Even for the sites, where ancient trees are venerated by people and are protected, their surroundings are not supportive of their existence in the long run. Activities like trimming branches, curtailing root growth and water percolation by cementing the base, temple/mosque/house/shop construction etc. cumulatively affect tree health and its future generation.

socio-economic changes we are losing our rural plant diversity which is often replaced by economically important species be it timber or cash crops. A pertinent example can be cited from road network establishment program. Aimed at greater connectivity and economic prosperity of even interior villages, the implementations are ecologically and environmentally insensitive in most places of India. Large numbers of good old trees are cut without giving a second thought and as compensation, we are getting Acacia, Eucalyptus, Casuarina, Peltophorum spp. For rural folk, these trees are financially acceptable as they grow fast, people are getting money for their maintenance and even for cutting and selling (Figure 3). On the flip side, nobody concerns about the soil quality deterioration, disruption in nutrient cycling, adverse impact on local fauna. Even for the sites, where ancient trees are venerated by people and are protected, their surroundings are not supportive of their existence in the long run. Activities like trimming branches, curtailing root growth and water percolation by cementing the base, temple/mosque/house/shop construction etc. cumulatively affect tree health and its future generation.

Urban landscape presents a more complex scenario mostly with a negative notion. Intense urban housing and transport infrastructure, space crunch, heterogeneous community, multiple lifestyle demands and political wills are major drivers for green space management. Many a time, the spreading canopy and apparent clumsiness of the old tree does not fit with the urban criteria of green space beautification. Obviously, felling and uprooting of old trees disturb us, but their absence from our lives is barely felt owing to a lack of awareness on their role in nature. Above all, environmental awareness is still at its nascent stage in urban society, the consensus is often restricted to pollution, solid waste management and tree planting, where the number counts, the species choice depends on what survive easily and grow faster.

In view of this socio-cultural and spatial background, the obvious questions are what is the importance of having an ancient tree in a landscape? Aren’t we doing plantation, establishing green place and following other sustainability measures? To seek the answers, we have to explore multiple aspects of human cultural history along with evidence-based ecology and environmental perspectives. Ecologically, ancient trees are Pandora’s box for us though in a positive note. Careful observation can reveal interesting sights of bats hanging inversely from the trees which are an important mediator of pollination and dispersal for many species, similarly, beehive may pose danger for some but they are the backbone for agri- and horticulture, without them, big industries can fall apart (Figure 4). You see a flock of birds resting on the trees, perhaps they are the long-distance flying birds or migratory birds who use these trees as halting place in their journey. Look into the caterpillar, insects, ants, grasshoppers, scorpions these members need a very minimal resource for their survival, an old tree is like a grandfather for them from where they are getting food, shelter and congenial atmosphere for home. Last but not least important, a big old tree means storage of carbon dioxide (a major greenhouse gas) in different forms for many years, therefore, contributes to keep our atmosphere clean. One can argue that these services are common to all well-grown trees, but for ancient trees they are the time-tested long-term establishments under different climatic and anthropogenic scenarios, which definitely have experience values.

the backbone for agri- and horticulture, without them, big industries can fall apart (Figure 4). You see a flock of birds resting on the trees, perhaps they are the long-distance flying birds or migratory birds who use these trees as halting place in their journey. Look into the caterpillar, insects, ants, grasshoppers, scorpions these members need a very minimal resource for their survival, an old tree is like a grandfather for them from where they are getting food, shelter and congenial atmosphere for home. Last but not least important, a big old tree means storage of carbon dioxide (a major greenhouse gas) in different forms for many years, therefore, contributes to keep our atmosphere clean. One can argue that these services are common to all well-grown trees, but for ancient trees they are the time-tested long-term establishments under different climatic and anthropogenic scenarios, which definitely have experience values.

Looking into the cultural history, trees demarcate human’s association with a particular place. For many of us with a rural or semi-urban background, nature had played an important role in our mental growth during the formative years. The gigantic and spreading appearance of the old trees are responsible for both the feeling of admiration and fear which perhaps the first lesson to understand the mightiness of nature. Simultaneously, observing the flock of birds and their nests, beehives, bats, squirrels, caterpillar, ants and countless other life forms under the big umbrella of the ancient tree also teaches us the lesson of inclusiveness. Likewise, our socio-religious activities (eg. marriage, naming ceremony, social lunch, festivals, get-together, after death rituals) centered around the tree build up the connection between the people and tree, in a broader sense with nature. Many indigenous communities relate themselves with a particular tree, a sign of cultural identity for them. Example can be drawn from pimpleys of Maharashtra (pipal or Ficus religiosa), Gaadas of Karnataka (kadamba, Neolamarkia cadamba), Umariyas from Madhya Pradesh (umar tree Ficus racemosa), Dhanik clan of Madhya Pradesh (dau tree, Anogeissus latifolia), Santal from Chotanagpur plateau (sal tree, Shorea robusta). In brief, consciously or sub-consciously ancient trees are entangled with our lives.

Old trees are omnipresent in literature, arts, religion, traditional forms but comprehensive studies on their environmental existence are still underexplored. Except for documentation and public outreach materials they are almost divorced in our research domain. Studies on old trees to evaluate their role in ecosystem especially in semi-urban and urban landscape are in dire need. On the same note, environmental awareness programs focusing on these ancient members should involve and sensitize people about their ecological and social values. The living heritage, the band of our green and mighty forefathers, should be protected for our biological and mental well-being as well as for posterity.

Acknowledgment

The author is thankful to Prof. M.D. Subash Chandran, Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES), Indian Institute of Science for reviewing the manuscript for its improvement and Dr. Avik Ray for his comments on the earlier versions.

Reference

- Gupta S.M (2001) Plant myths and traditions in India. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Private Limited. ISBN 81-215-1007-4.

- Upadhyaya K.D (1964) Indian botanical folklore. Asian Folklore Studies 23(2):15-34.

About Author:

About baobab tree

Found the article very informative and deep. Thanks for correlating ecology and cultural heritage.

Here I see a photo of a stone Shivalinga (maybe a combination of lingas) below the auxiliary roots of a banyan tree with the lower portion of the auxiliary roots painted white. What is the exact location of this place? Thanks in advance for your answer.