Jharkhand, one of the mineral-rich states of India, is the abode of various Adivasi communities. With the advent of resource hungry technocentric civilisation, the lands of Jharkhand became precious for ‘development’. Due to the development projects the Adivasis and Moolvasis of Jharkhand have been facing the trauma of displacement. The rehabilitation programs and compensation packages have failed to protect the traditional, cultural, social, and economic interests of the Adivasi communities. These failures indicate the fact that the policymakers could not asses the value of the Adivasi land from the Adivasi perspective. Dayamani Barla in her book Kissanon ki Jameen Loot Kis Ke Liye writes:

“..सवाल है किसका मुआवजा मिलेगा? क्य आदिवासियों, मूलवासियों, किसानों, कारीग्रों की भाषा-संस्कृति को? सामाजिक मुल्यों को? आदिवासियों के इतिहास को? इंके पारम्परिक मुल्य ? प्रकृतिमूलक समाज के परम्परागत ज्ञान-विज्ञान,नोलेज और कला को? ..सर्ना-ससनदीरी का? क्या कलकल बहती नदियों का? ..क्या शुद्ध ह्वा का? आखिर किस्का मूआवजा ? और किसका पुनर्वास? जबकि आदिवासी समाज मानता है कि इनके सामाजिक. सांस्कृतिक,आर्थिक, धार्मिक अस्तित्व, सरना-ससनदिरी, को न तो पुनर्वासित किया जा सकता है और न हि किसी मूआवजा से भरा जा सकता है”. (Barla 19-20)

“ The question is of what things we would get as compensation? Of the linguistic culture of Adivasis, Moolvasis, peasants, artisans? Of our social values? Of the history of adivasis? Of the traditional values of those things? Of the science-technology, knowledge, art of environment centric society? Of sarna-sasandiri? Of that babbling river which is flowing? Of pure air? What things? And also the rehabilitation of what? Whereas Adivasi society believes that the social, cultural, economic, religious beingness and the sarna-sasandiri are neither can be rehabilitated nor can be compensated?

Dayamani Barla’s words focus on the way Adivasi society understands the landscape. The landscape falls within the realms of physical, psychological, and emotional relationships. To understand the nuances of the relationship, we may try to engage with the meanings/interpretations of the term Sasandiri from the perspective of Munda community of Chota Nagpur Plateau.

The Munda people probably descended from Austroasiatic linguistic group from Southeast Asia. Initially, they were nomadic hunters. With the time they became farmers but did not sever their bonds with the forest (Wikipedia).

Sasandiri is the place where the Mundas bury the bones of the ancestors of a Kili[1] under stone slabs. The stone-slabs are known as Sasandiri. But it is not meant for anyone living in the village. If the deceased belong to the family of the first settler or Khuntkattidar of that village, only then her or his bones get a place in Sasandiri. The bones of a deceased member of a Kili died ‘‘during the preceding twelve months’ were ceremonially buried in the family sasan’’on ‘Jang-topa’ day. Jang-topa ceremony is generally performed in the month of January -February (Pous-Magh) ( Roy 2010).

Hence the meaning of Sasandiri to a Munda person is not just a burial ground. It means the inheritance of the land. It is also a space of continuity and symbol of adivasi identity-the identity of the first settler. A khuntkattidar was the one who settled the first village after finding the place suitable for continuing Munda way of living. If we look at the prayers that are chanted by Pahan during various festivals and rituals, we can see the prayers along with the bongas (spirits) call ‘ancestors, foreparents, and elders’ to join the ceremonies, to bless the living beings. The followers of Adi-dharam believe that the living ones coexist with the deceased spirits. The departed souls do not abode for heaven or hell. Instead, the dead one comes back at the house, and the soul of the dead through the ritual and prayer gets included in the world of the ancestors.

Interestingly, the ceremony of ‘Umbul -ader’ or ‘return of shadow’ is a ritual of celebration. This day the family members bring back the soul of the deceased. The relatives join the ceremony. After the sun is down, accompanied with drums selected persons to go to village Masan to bring back the shadow of the deceased. Until the soul of the deceased comes back to the house, relatives make a small hut at the Masan for the dwelling of the deceased. On the day of Umbul later, those who go to bring back the shadows burn the hut and bring back the shadow to the ‘ancestor corner’ of the house. Before entering the house with the shadow, men declare that they bring happiness. The ceremony reveals the importance of burial ground or home to the Munda community. An emotional and historical sense of belonging is attached to the Sasandiri. The compensation structure does not have the tools to understand, acknowledge, and calculate the value of the place that is an integral part of Adivasi society. To Dayamani Barla Sasandiri is one of the symbols of Munda identity. The place is the abode of ancestors. It also carries the truth that the living souls would meet the deceased and it is also a place of direct connection with the ancestors who live in shadow and also in memory. ‘Everything would wither’ she repeated the sentence twice while describing the importance of Sasandiri in the living space of Munda community.

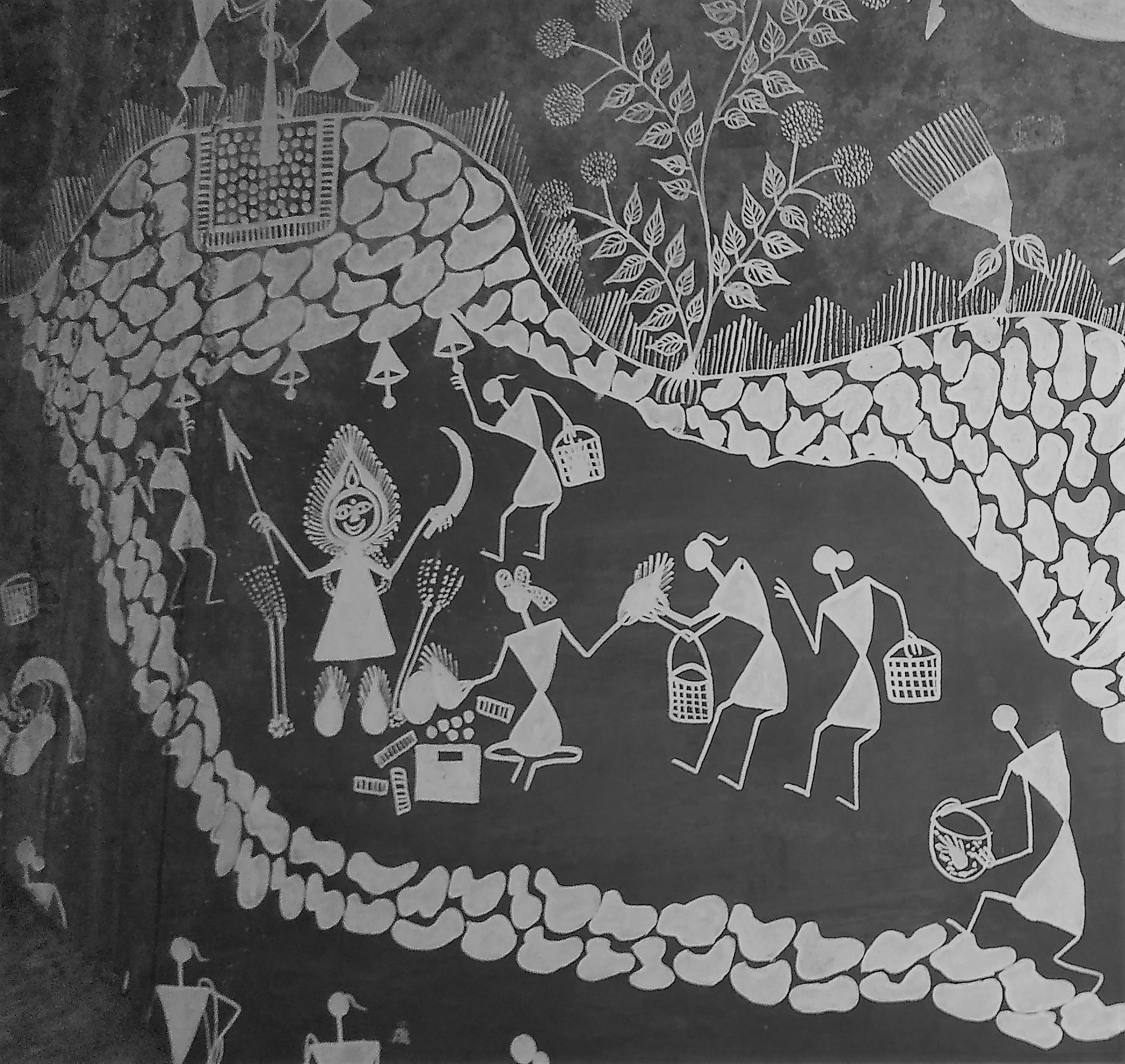

Hence, Sasandiri is the actual place that holds memories of elders and histories of Munda elders’ transition from one place to another. Here the members of Khuntkattidars reunite once in a year and perform the cultural practice. The site also symbolises Munda tradition. The image of sharing the production of land with the ancestors situates the very place as one of the repositories of connection. Sasandiri and agricultural lands in the narrative of Dayamani become an integral part of adi-dharam– the Munda way of living. The dead ones coexist with the human species because the other world is a demarcated place within the village. This coexistence is also the part of Munda identity.

From this perspective, one must read the words of Dayamani Barla once again. She is talking about a Munda way of life that thrives on relationships that are physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual. Negation of any of these relationships would be a negation of indigenous existence.

Reference :

1) Barla D (2016) Kissano Ki Jameen Loot Kis e Liye? Ranchi: Adivasi- Moolvasi Astitva Raksha Manch, Print

2) Roy SC (2010) The Mundas and Their Country. Ranchi, 4th Reprint.

3) Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munda_people

[1] “ The Munda tribe is divided into a large number of exogamous groups called kilis. According to Munda tradition, all the members of the same kili are descended from one common ancestor” (Roy. 217).

About Author: