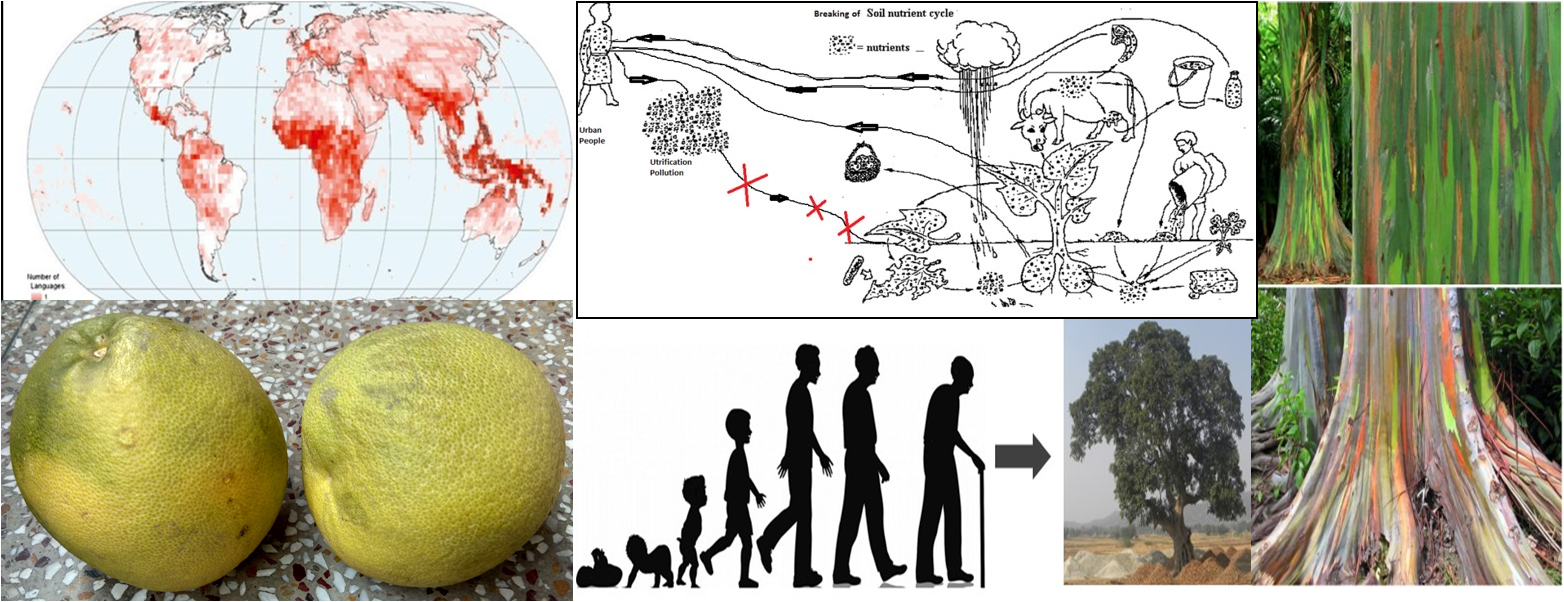

Death: Environment friendly

Death is the unavoidable and intriguing phase of human life. It reminds us of our very biological identity in the natural world leaving apart our supremacy over the ecosystem.  This very biological entity of the human being increasingly creating trouble even after death!!!! Surprised? But it’s true. Although death means the end of everything but mortal remains are there, usually treated according to our socio-cultural and religious beliefs. Burial of dead body is a prevalent practice among many communities following different religions and the procedure is a lengthy one from dead body processing to the selection of burial ground. However, in the backdrop of population explosion, space crunch and environmental hazards, traditional burial processes seem to be inefficient in many ways. Application of embalming chemicals, growing demands of wooden caskets and burial places complicated the after-death rituals manifold.

This very biological entity of the human being increasingly creating trouble even after death!!!! Surprised? But it’s true. Although death means the end of everything but mortal remains are there, usually treated according to our socio-cultural and religious beliefs. Burial of dead body is a prevalent practice among many communities following different religions and the procedure is a lengthy one from dead body processing to the selection of burial ground. However, in the backdrop of population explosion, space crunch and environmental hazards, traditional burial processes seem to be inefficient in many ways. Application of embalming chemicals, growing demands of wooden caskets and burial places complicated the after-death rituals manifold.

To ease the operation especially from environmental viewpoint, the concept of “green burial” becoming popular in recent years. Among different methods, cremation with recycling is an interesting idea. Here, after cremation, the remnants have grounded into powdery masses (known as Ash) and transferred to containers. The remnant is used as planting material for individual or mass plantation drive. The advantage is one can completely avoid the lengthy and complicated after death procedures to maintain the dead body, there is no requirement for burial place (a burning problem in the populated world) and no environmental hazard in terms of embalming chemicals or other associated items. In a way, our mortal remain is recycled in nature in a different form (here it is a plant) with an eco-friendly tag.

Photo: Google Image, Rajasri Ray

Collector: Rajasri Ray

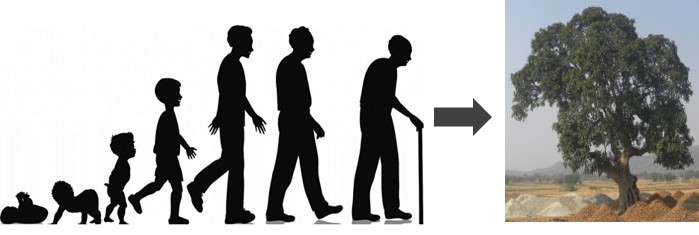

Pomelo, Limau besar, or Jambura – whats in a name?

Sweet and mystic smell of Citrus flowers, fruits, and leaves have mesmerized people and fragrance-hunters alike. But, you may be unaware of the enchanting smell of Cirtus maxima or Citrus grandis – surely you have twisted and laid your tongue on its sweet and juicy fruit.

of Cirtus maxima or Citrus grandis – surely you have twisted and laid your tongue on its sweet and juicy fruit.

Call it in any name depending on your ethnicity and origin, e.g., Pomelo or Pumelo (English), Pampelmuse (German), Pampa limasu (Tamil), Batabi / Jambura (Bengali / Hindi), Chakotara (Hindi), Limau besar or Limau betawi (Malay), Jabong (Hawaii) or Jambola (broadly south Asia). Its size and shape vary, so does sweetness – red rind generally being sweeter than white ones. Scientifically named as Citrus maxima or Citrus grandis of Rutaceae family, its native range is spread across south and south-east Asia where it was domesticated, but contentions prevail. What followed domestication was long and complex history of translocation; traveling great distance, sometimes crossing borders, traversing oceans and continents largely facilitated by human movement; finally reaching Europe and America from the Orient. So, it landed on distant palettes, tickled their taste buds, and slowly mingled into local food culture. Recent cutting-edge scientific research suggests, Cirus maxima is a key species that can claim many modern edible citrus species as its offspring; so, it seems it has not only contributed to common and modern-day pomelo, its role – as mother or at least a part-parent of all the oranges – is not an exaggeration.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, the fruit has not achieved high  commercial importance as sweet orange or lime. But, it is largely grown in home gardens and savored locally. It has been culturally associated with various festivals in India and is valued highly during the festive seasons; e.g., in Chhath Puja (Bihar and Jharkhand), Vishwakarma and Durga Puja (Tripura, Assam and West Bengal). Also, there are many local ecotypes cherished and earned fame, such as Devenahalli Pomelo in rural Bangalore, Karnataka that won its GI tag recently, far-flung village of Medziphema in Nagaland is also a proud grower of sweeter pomelo, and so on – remains our lesser-known agrobiological heritage conserved at farm for posterity.

commercial importance as sweet orange or lime. But, it is largely grown in home gardens and savored locally. It has been culturally associated with various festivals in India and is valued highly during the festive seasons; e.g., in Chhath Puja (Bihar and Jharkhand), Vishwakarma and Durga Puja (Tripura, Assam and West Bengal). Also, there are many local ecotypes cherished and earned fame, such as Devenahalli Pomelo in rural Bangalore, Karnataka that won its GI tag recently, far-flung village of Medziphema in Nagaland is also a proud grower of sweeter pomelo, and so on – remains our lesser-known agrobiological heritage conserved at farm for posterity.

Photo: Avik Ray

Collector: Avik Ray

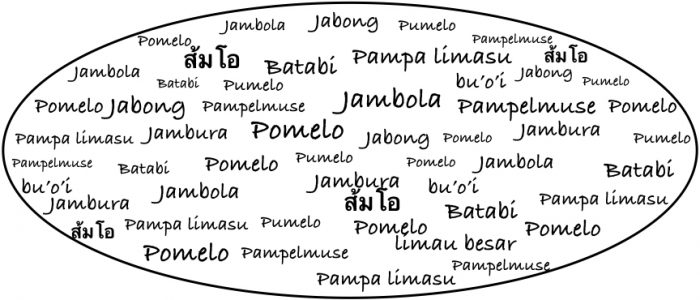

Rainbow on a tree!!

If there is a contest of the most colorful tree on earth, rainbow eucalyptus  (Eucalyptus deglupta, family: Myrtaceae) will surely have topped!! These trees also popularly called as Mindanao gum, have intriguingly multihued bark. On shedding of bark during summer, it starts revealing light green color beneath which gradually turns to dark green and to shades of blue, pink, red, purple, orange just like a rainbow. The tree is a native to the tropical areas of New Guinea, Surinam, Sulawesi

(Eucalyptus deglupta, family: Myrtaceae) will surely have topped!! These trees also popularly called as Mindanao gum, have intriguingly multihued bark. On shedding of bark during summer, it starts revealing light green color beneath which gradually turns to dark green and to shades of blue, pink, red, purple, orange just like a rainbow. The tree is a native to the tropical areas of New Guinea, Surinam, Sulawesi

and Mindanao though it is now grown as an ornamental tree throughout the world. Interestingly the colors are not so bright outside its native range. Very little is known about why it changes color so dramatically. Working theory states that each bark layer of this plant has a single cell thick transparent cover. With the passage of time, this layer gets rinsed with variously colored tannins. Accumulation of these tannins and degradation of chlorophyll finally lead to this vibrantly colored bark layers.

Source: Wikipedia

Collector: Debarati Chakraborty

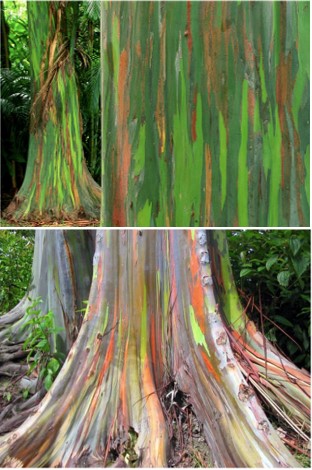

The linguistic connection of biodiversity

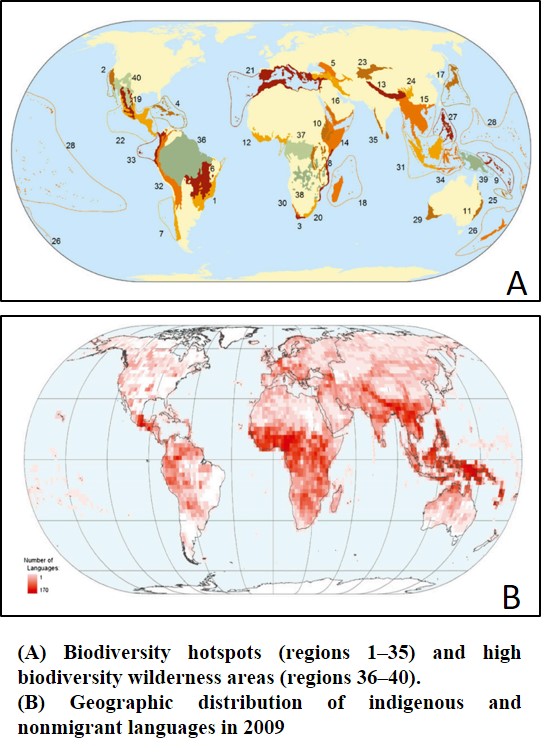

Biodiversity, at first glance, seems to be connected with only living systems and their relation with surroundings, only a thorough look can reveal the presence of a myriad of factors spread below the surface. Language is vital among them. In general, language builds up the bond  between people, acts as identity for a community and a powerful tool for the overall improvement of society. However, the connection with biodiversity has been recognized recently and is an active field of research. Biodiversity components like vernacular names of flora and fauna, place names, rituals, taboos and most importantly community association are interwoven with the cultural and linguistic identity of a community. The environmental and ecological association of the people with nature is best expressed by his/her language and manifested through lifestyle, religious, and cultural practices. Moreover, the information is dispersed at intercommunity and intergenerational levels through language only. In a broader sense, it plays a prominent role in natural resource and landscape management, resource allocation strategy, and intercommunity relation in terms of resource acquisition and sharing. Global studies suggest that the pattern of linguistic diversity is well corroborated with species diversity, even, biological hotspots are good reservoirs of language diversity too (accounting 70% of the total languages on the earth and high endemism). Likely reasons for co-occurrence are many and locality specific, but one important factor is the socio-cultural association of the indigenous communities with biodiversity where language is a major vehicle of tradition and management. The loss of language or language shift is therefore slow but irreplaceable damage to biodiversity as it affects the available knowledge base of the region and ecosystem. If a language becomes extinct or suppressed by a dominant counterpart, the vocabulary associated with nature and natural resources is also affected due to the gradual decline of usage, incomprehensibility, and the lack of documentation. Subsequently, the specific knowledge base which is best expressed through that language becomes inaccessible and finally lost.

between people, acts as identity for a community and a powerful tool for the overall improvement of society. However, the connection with biodiversity has been recognized recently and is an active field of research. Biodiversity components like vernacular names of flora and fauna, place names, rituals, taboos and most importantly community association are interwoven with the cultural and linguistic identity of a community. The environmental and ecological association of the people with nature is best expressed by his/her language and manifested through lifestyle, religious, and cultural practices. Moreover, the information is dispersed at intercommunity and intergenerational levels through language only. In a broader sense, it plays a prominent role in natural resource and landscape management, resource allocation strategy, and intercommunity relation in terms of resource acquisition and sharing. Global studies suggest that the pattern of linguistic diversity is well corroborated with species diversity, even, biological hotspots are good reservoirs of language diversity too (accounting 70% of the total languages on the earth and high endemism). Likely reasons for co-occurrence are many and locality specific, but one important factor is the socio-cultural association of the indigenous communities with biodiversity where language is a major vehicle of tradition and management. The loss of language or language shift is therefore slow but irreplaceable damage to biodiversity as it affects the available knowledge base of the region and ecosystem. If a language becomes extinct or suppressed by a dominant counterpart, the vocabulary associated with nature and natural resources is also affected due to the gradual decline of usage, incomprehensibility, and the lack of documentation. Subsequently, the specific knowledge base which is best expressed through that language becomes inaccessible and finally lost.

Source and Image: www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1117511109

Collector: Rajasri Ray

The Silent Autumn – festivity with soil impoverishment

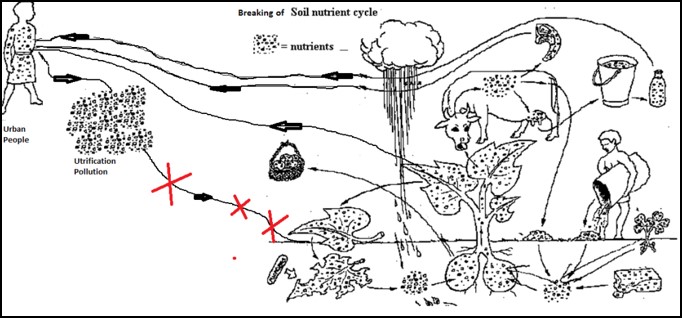

The great Indian festive season starts from September and continues up to December. The autumn festivals have a traditional linkage with harvesting season of the country. The festivals come as a long expected relief at the end of agricultural workload.  However, this happy milieu of festivity with agricultural products has some harmful side-effects in its own credit. Present day harvesting season is coupled with the period of disruption of bio-geochemical cycles – the cycling process of soil nutrients. Sounds interesting? Yes, it is but is quite alarming at the same time.

However, this happy milieu of festivity with agricultural products has some harmful side-effects in its own credit. Present day harvesting season is coupled with the period of disruption of bio-geochemical cycles – the cycling process of soil nutrients. Sounds interesting? Yes, it is but is quite alarming at the same time.

In our school days, we learned that the plant receives several elements like potassium (K) magnesium (Mg) molybdenum (Mo) zinc (Zn) etc from soil; needless to say, that the same is true for the crops also. Those elements are transferred from plant to animal body when animals consume plant as a food and in the same way pass from herbivorous to carnivorous animals. Those elements are essential for living organisms for growth and reproduction. After death, the plant or animal bodies or excreta are decomposed by a plethora of organisms and subsequently these elements come back into the soil.

Now, if agricultural products are consumed at a place nearby the site of production, then the nutrient may return through the complex process of recycling. But if it is consumed at a geographically distant place the nutrients can never come back to the production field through the natural cycling. Thus the fertility of soil becomes undone that we may call a metabolic rift.

One may argue that the transfer of agricultural product is a historical event, so is the transfer of nutrients. Whether the issue is also historic? It is historic beyond any doubt, but magnitude plays a key role in the current scenario. With the advent of city-centric civilization, there is an exponential increase in population, urbanization and city-centric resource gathering practices which affect nature and natural resources in different manner.

A very basic calculation on rice and wheat consumption in Indian household shows that yearly ~ 80013 metric ton potassium (K) transfers from agricultural field to cities (based on 2001 census data and 1999-2000 consumption profile). Adding other crops, the amount will be increased manifold. This amount of potassium never comes back to the soil through natural nutrient cycling and external application of fertilizers. The fate is the same for the other elements absorbed by the crops from the field and exported to the town. In this way, several tons of different micronutrients (i.e., Fe, Ca, Mg, Cu, Mn, Mo, Zn names please) are regularly lost from the agricultural field causing soil impoverishment at a massive scale.

To many, chemical fertilizers seem to be a solution but they invite several other problems. Major fertilizers (N P K) can’t supply micronutrients. Recommendation of micronutrient fertilizers is a matter of dispute as there is very little difference between the density of micronutrient ideal for production and the density which bring toxic effect. After six decades of green revolution different agricultural field of our country is now suffering from over density of some nutrients and deficiency of others. The festive season could be silent in not-so-far future.

Source : Foster J.B. (2000) Marx’s Ecology Materialism and nature, Monthly Review Foundation

Photo: http://www.uq.edu.au/_School_Science_Lessons/6.65.2.GIF

Collector: Abhra Chakraborti