Red meat or white meat? No, I want BLACK meat!

Yes, the inhabitants of Jhabua and Dhar districts of Madhya Pradesh can enjoy black meat of Kadaknath chicken which is locally appreciated as Kali Masi (which means ‘fowl having black flesh’). Although the old chicks are bluish to black, adults are mostly black or bluish black in color. The comb, wattle, and tongues are purplish and feet are greyish.  The striking feature of this bird is many of the internal organs are black in color. The black coloration is due to excess deposition of melanin pigment skin and several other tissues or organs such as blood vessels, muscles, gonads and tracheas because of a genetic condition known as fibromelanosis or dermal hyperpigmentation. Black breeds are also found in other domesticated chicken breeds, such as Ayam Cemani in Indonesia, Kadakhnath in India, Black H’Mong in Vietnam, Argentinean, Tuzo type in Argentina, and Svartho ̈na in Sweden.

The striking feature of this bird is many of the internal organs are black in color. The black coloration is due to excess deposition of melanin pigment skin and several other tissues or organs such as blood vessels, muscles, gonads and tracheas because of a genetic condition known as fibromelanosis or dermal hyperpigmentation. Black breeds are also found in other domesticated chicken breeds, such as Ayam Cemani in Indonesia, Kadakhnath in India, Black H’Mong in Vietnam, Argentinean, Tuzo type in Argentina, and Svartho ̈na in Sweden.

Kadaknath is a native breed whose range extends from Madhya Pradesh to the neighboring districts of Rajasthan and Gujarat. Considered as sacred among tribals, they used to rear this bird for sacrificial purpose during the festivals. The black meat is not only taste bud tickler but also has high nutritive and medicinal value. No wonder, this famous Kadaknath chicken has earned a geographical indication (GI) tag that denotes that the product is culturally associated with a specific geographical area, and often enhances its commercial value. However, largely owing to its high consumption rate its population has declined drastically in recent times. A ray of hope: an organized breeding is in full swing in some areas that may cater consumer needs.

So, instead of shuttling between red and white, let’s go for black (not dog) chicken.

Photo: Press Trust of India (PTI)

Collector: Avik Ray

Microscopic Da Vincis and the Curious Case of Photokinetics

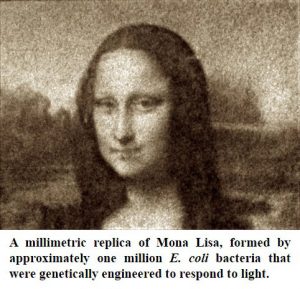

Leonardo da Vinci, the Renaissance polymath from Italy, might have left us in 1519 AD, but a million of microscopic da Vincis have painted a miniature replica of his masterpiece Mona Lisa in 2018! Sounds crazy? Hold your thoughts and ask Dr. Giacomo Frangipane, a post-doctoral researcher of physics at the University of Rome, Italy, if you don’t believe me!

The minute da Vincis in question are none other than the famous Escherichia coli bacteria, found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded animals naturally and a favourite among scientists. These bacteria (many strains) are mobile and they move by the help of a specialised, whip-like appendage called flagellum (plural: flagella). Flagella are primarily used for locomotion by single-cell organisms, and they are propelled by a motor, a rotary engine made of proteins. Like any other engine, this motor requires energy to function, and in the case of E. coli it operates by using oxygen. Recently, scientists discovered a protein (proteorhodopsin) in some marine bacteria which absorbs light to power the motor in their flagella, through a process called photokinetics.

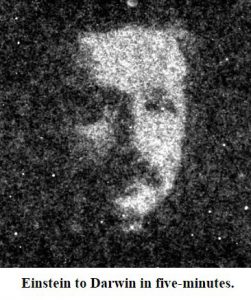

All good and fine. So, how did the E. coli paint the Mona Lisa? The clue lies in the light! To remotely control their movement, Frangipane and colleagues genetically modified their E. coli to produce the photo-sensitive proteorhodopsin. This made the otherwise oxygen-modulated flagella to now move by the help of ambient light, much like mounting a solar panel on a car!  Next starts the painting. For that the scientists projected light through a microscope lens, and explored how the bacteria change their speed while swimming through areas with varying degrees of illumination. “Much like pedestrians who slow down their walking speed when they encounter a crowd, or cars that are stuck in traffic, swimming bacteria will spend more time in slower regions than in faster ones,” explained Frangipane. “We wanted to exploit this phenomenon to see if we could shape the concentration of bacteria using light.” They projected the light uniformly onto a layer of bacterial cells for five minutes, before exposing them to a more complex light pattern – a negative image of the Mona Lisa. They found that bacteria started to concentrate in the dark regions of the image while moving out from the more illuminated areas. After four minutes, a recognisable bacterial replica of the masterpiece emerged. After creating the Mona Lisa, Frangipane and his team manipulated the E. coli into a face-changing portrait that transformed from a likeness of Albert Einstein to that of Charles Darwin in just five minutes

Next starts the painting. For that the scientists projected light through a microscope lens, and explored how the bacteria change their speed while swimming through areas with varying degrees of illumination. “Much like pedestrians who slow down their walking speed when they encounter a crowd, or cars that are stuck in traffic, swimming bacteria will spend more time in slower regions than in faster ones,” explained Frangipane. “We wanted to exploit this phenomenon to see if we could shape the concentration of bacteria using light.” They projected the light uniformly onto a layer of bacterial cells for five minutes, before exposing them to a more complex light pattern – a negative image of the Mona Lisa. They found that bacteria started to concentrate in the dark regions of the image while moving out from the more illuminated areas. After four minutes, a recognisable bacterial replica of the masterpiece emerged. After creating the Mona Lisa, Frangipane and his team manipulated the E. coli into a face-changing portrait that transformed from a likeness of Albert Einstein to that of Charles Darwin in just five minutes

Although using photokinetic bacteria to paint famous portraits is fun, there are serious implications of this research as intended by the scientists. Controlling bacteria in this way means it could be possible to use them as microbricks for building the next generation of microscopic devices. For example, they could be made to surround a larger object such as a machine part or a drug carrier, and then used as living propellers to transport it where it is needed. Furthermore, they can be applied for creation of biomechanical structure or microdevices for the transport of small biological cargoes inside miniaturised laboratories.

Source and Photo:

- Original research: Dynamic density shaping of photokinetic E. coli

Collector: Subhajit Saha

Galar putul – story of a dying industry

The enriched cultural heritage of Bengal is resonated not only in old architectures, literature, paintings and cuisines but also in its unique toys. Galar putul – shellac coated clay dolls is one such heritage toy. These bright coloured toys represent a diverse socio-cultural history of the rural Bengal. The toy making procedure itself is a delicate and skilled artwork. Soil for making galar putul are collected from termite hills as it is relatively gravel free and adhesive in nature. The moist soil is kneaded, cleaned, pressed and pinched to form models. Baked models are coated with long sticks of painted shellac. Finally, Guna work (thin shellac threads making from lac sticks) is done to decorate the figurines. Nose, eye-ball, hair, moustache, ear-ornaments, etc. are formed by coloured shellac drops. The toys include small dolls, elephant rider (hatishowar), horse rider (ghorashowar), animals, fruits, votive figurines or folk goddesses like shasthi. A full range of these toys represent the contemporary society and art forms of the south-western rural Bengal. The specific geographic conglomeration of this art form is due to the availability of natural resources in the region. Shellac, the essential raw ingredient for Galar Putul is a resin secreted by the female lac bug (Kerria lacca) while sucking tree sap. The insect secrets it as a tunnel-like tube while moving through the tree branches. The main host trees used for its cultivation are Palash (Butea monosperma), Kul (Ziziphus mauritiana) and Kusum (Schleichera oleosa). Mature crop along with branches are harvested, lac encrustations (sticklac) are scraped off and processed to form shellac. Generally, the lands unsuitable for agricultural purposes are used for lac cultivation. Lac cultivation is being done in Bengal since ancient times in the districts of Purulia, Midnapore, Bankura & Birbhum. Lac industry was in its glory days back in 1787, when David Erskin founded Erskin & Co. company in Illumbazar, Birbhum. It lasted till 1882. But situation declined with the shortage of raw material and competition from other toys by 1920 when many artists have forsaken the profession. Rabindranath Tagore attempted to revive the art by holding training sessions at Sriniketan but the situation didn’t improve.

These bright coloured toys represent a diverse socio-cultural history of the rural Bengal. The toy making procedure itself is a delicate and skilled artwork. Soil for making galar putul are collected from termite hills as it is relatively gravel free and adhesive in nature. The moist soil is kneaded, cleaned, pressed and pinched to form models. Baked models are coated with long sticks of painted shellac. Finally, Guna work (thin shellac threads making from lac sticks) is done to decorate the figurines. Nose, eye-ball, hair, moustache, ear-ornaments, etc. are formed by coloured shellac drops. The toys include small dolls, elephant rider (hatishowar), horse rider (ghorashowar), animals, fruits, votive figurines or folk goddesses like shasthi. A full range of these toys represent the contemporary society and art forms of the south-western rural Bengal. The specific geographic conglomeration of this art form is due to the availability of natural resources in the region. Shellac, the essential raw ingredient for Galar Putul is a resin secreted by the female lac bug (Kerria lacca) while sucking tree sap. The insect secrets it as a tunnel-like tube while moving through the tree branches. The main host trees used for its cultivation are Palash (Butea monosperma), Kul (Ziziphus mauritiana) and Kusum (Schleichera oleosa). Mature crop along with branches are harvested, lac encrustations (sticklac) are scraped off and processed to form shellac. Generally, the lands unsuitable for agricultural purposes are used for lac cultivation. Lac cultivation is being done in Bengal since ancient times in the districts of Purulia, Midnapore, Bankura & Birbhum. Lac industry was in its glory days back in 1787, when David Erskin founded Erskin & Co. company in Illumbazar, Birbhum. It lasted till 1882. But situation declined with the shortage of raw material and competition from other toys by 1920 when many artists have forsaken the profession. Rabindranath Tagore attempted to revive the art by holding training sessions at Sriniketan but the situation didn’t improve.

Nuris of Birbhum and Shankharis of Bankura and Medinipur districts are the communities engaged in making galar putul. Sadly, this colourful toy industry has been losing the battle against cheap plastic dolls. Most of the artisans have changed their professions and their remains very few to carry forward the legacy of this folk art.

Photo: Abhik Sarkar, Wikipedia

Collector: Debarati Chakraborty

The rolling balls of life

‘Wild Wild West’ – hearing these words we immediately link ourselves with the Western arid North America with its rugged terrain, dry environment, rolling weeds and obviously cowboys in hats and tights. Thanks to Hollywood for this globally acknowledged collage.  One of the obvious components of this picture is rolling weeds aka Tumbleweeds. The Tumbleweeds are bushy plants/plant bodies which after finishing their reproductive function becomes dry and gradually detach themselves from their place of association. The detached bush often appears as dry and thorny ball of various sizes then tumbles by the wind and rolls over a great distance along the deserted landscape. The underlying reason of this curious activity is the dispersal of seeds so that they can spread across a vast area and can avoid harsh competition for resources. Moreover, this frantic movement helps these plants to establish their colony throughout Western North America and forces people to take them as a serious menace to public life.

One of the obvious components of this picture is rolling weeds aka Tumbleweeds. The Tumbleweeds are bushy plants/plant bodies which after finishing their reproductive function becomes dry and gradually detach themselves from their place of association. The detached bush often appears as dry and thorny ball of various sizes then tumbles by the wind and rolls over a great distance along the deserted landscape. The underlying reason of this curious activity is the dispersal of seeds so that they can spread across a vast area and can avoid harsh competition for resources. Moreover, this frantic movement helps these plants to establish their colony throughout Western North America and forces people to take them as a serious menace to public life.

This tumbling activity has been reported from a number  of flowering plants and even from lower group of plants like fungi and pteridophytes. Some well-known members are, Salsola kali subsp. tragus (Russian thistle), Artiplex rosea (tumbling oracle), Centaurea diffusa (tumble knapweed), Gypsophila paniculata (baby’s breath), Selaginella lepidophylla (pteridophytes) and members of earthstar mushroom family (Geastraceae).

of flowering plants and even from lower group of plants like fungi and pteridophytes. Some well-known members are, Salsola kali subsp. tragus (Russian thistle), Artiplex rosea (tumbling oracle), Centaurea diffusa (tumble knapweed), Gypsophila paniculata (baby’s breath), Selaginella lepidophylla (pteridophytes) and members of earthstar mushroom family (Geastraceae).

Tumbleweed has a significant presence in American socio-cultural life especially in western part of the continent. Be it music, literature, painting or movie, the Western arid landscape has been vividly portrayed with these moving plant forms.

Source : Wikipedia

Photo: Getty images, New York Post

Collector: Rajasri Ray

Biodiversity through sound

The term “Biodiversity” becomes popular to all niches of the society, thanks to active media involvement for awareness generation. Today, we all know that biodiversity encompasses variety of life forms, ranges from microscopic to macroscopic, unicellular to multicellular, gene to biome level. It is not restricted in species check list preparation, it also includes distribution, function, maintenance, evolution, society, economics even politics.

The term “Biodiversity” becomes popular to all niches of the society, thanks to active media involvement for awareness generation. Today, we all know that biodiversity encompasses variety of life forms, ranges from microscopic to macroscopic, unicellular to multicellular, gene to biome level. It is not restricted in species check list preparation, it also includes distribution, function, maintenance, evolution, society, economics even politics.

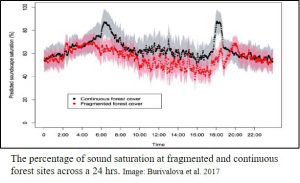

The basic unit of biodiversity measurement is species. However, the concept is ever changing and there are multiple ways to measure the biodiversity of any area of interest. But “Sound”!!!!!! How can sound help us to measure the state of biodiversity in any particular area?  It is possible, at least recent research says so. In Papua New Guinea, a comparative study on eco-acoustic profile of fragmented and continuous forests has shown that there are distinct differences in dawn and dusk choruses at these forests. While searching for the reason behind these differences, ecologists uncovered an interesting point: forest fragmentation seems to have a major role in this difference. It has been detected that continuous and less disturbed forest areas have more saturated and complex soundscape (i.e. more complex and diverse acoustic relationship among organisms) than its fragmented and disturbed counterparts. The reason behind this richer soundscape seems to be presence of diverse insect and avian communities responsible for this grand opera whereas fragmented forests are impoverished in this regard. Interestingly, conventional estimation of avian diversity in fragmented forests has not shown much decline in avian members. To solve this riddle, researchers opined that, time and space constrained conventional methods may not be able to capture the entire spectrum of biodiversity, a problem, can be complemented through acoustic approach which is cost effective and result oriented.

It is possible, at least recent research says so. In Papua New Guinea, a comparative study on eco-acoustic profile of fragmented and continuous forests has shown that there are distinct differences in dawn and dusk choruses at these forests. While searching for the reason behind these differences, ecologists uncovered an interesting point: forest fragmentation seems to have a major role in this difference. It has been detected that continuous and less disturbed forest areas have more saturated and complex soundscape (i.e. more complex and diverse acoustic relationship among organisms) than its fragmented and disturbed counterparts. The reason behind this richer soundscape seems to be presence of diverse insect and avian communities responsible for this grand opera whereas fragmented forests are impoverished in this regard. Interestingly, conventional estimation of avian diversity in fragmented forests has not shown much decline in avian members. To solve this riddle, researchers opined that, time and space constrained conventional methods may not be able to capture the entire spectrum of biodiversity, a problem, can be complemented through acoustic approach which is cost effective and result oriented.

Photo: Burivalova et al. 2017(fig1), Rajasri Ray (fig2)

Collector: Rajasri Ray