I think I first came across with the word sustainability in a Bengali science magazine meant for the teenagers. It was the first half of nineties. India was gearing itself for another word-Globalization. The naivety of the tender age made me believe that the word sustainability falls into the domain of science. The absence of any kind of serious discussion on sustainability in the everyday living of middle-class Bengali family, I vaguely understood that scientists,like the superheroes, would save our planet from unsustainability which to many of us was solely air, water, and soil pollution by inventing some wonderful machines. The myth of machines was so dominant that I was not ready to believe that technology could exist outside heavy machineries. Slowly but surely my a change has been perturbing in our surrounding. The more newer technology is getting into our lives, the more was the change.

The change directly affected me while I was staying in Ranchi-the state capital of Jharkhand. One summer the deep well that was supplying the water to five families including our landlord just got dried. The natural water reservoirs of Ranchi were also in that summer facing shortage of water. Our landlord like others in the locality went for installing a more powerful pump machine that would suck water from the deep down of earth’s bosom. We had to pay some extra money to bear the cost. The technology available to us-the common men- was failing to give the Ranchi people back the good old days’ abundance of water. The memories poured in to let the new generation know how it was a place of comfort with a cool weather, lots of trees and almost daily rains. The well never dried up even during the hottest months of summer. The stories were swelling and so the quarrels over water in the nearby slums. The lament over new high rises, population rise, unplanned and ruthless chopping down of trees was there in the air of the Ranchi in that very summer. But every lament ended up equivocally with a single conclusion that people had no choice left but to welcome the development which was the primal cause of depletion of water resources. The situation appeared to me as the tragic impasse. In tragic impasse, the protagonist is left with no choice but to face the doom in her life. There is no hope for future. She has to bear the burdens of life with just a memory of a comfortable past. Ironically, the technology that are available in the capital controlled market is not designed to provide a panacea.

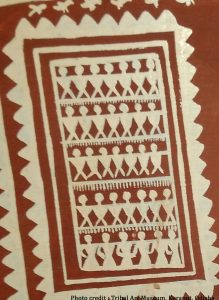

Imbued with this memory of Ranchi city, later in my life, I met few Adivasi women who took a leading role in the resistance movement against development-induced displacement. The women unequivocally expressed their resentment against development project. Development projects, according to them, would destroy the forest, land, and water- the three major components of Adivasi way of living. As long as the forest, river, and land are thriving, so will thrive the Adivasi societies- each of them pitched the same line in their own way. Clearly, the line reflects a hope for future. The women joined the movement to sustain her community’s life in the long run. They chose self-reliance over tech-dependency because that according to them ensures the food-security and sovereignty of their progenies. Why the women did not buy the narration of development like the Ranchi people? Why they chose to retain the culture of conserving the natural resources? Does it mean that our Adivasi communities have long developed an ideology of sustainability and shaped a culture around it?

The questions reminded me a line from Annadamangal , one of the stalwart literary creations in ‘medieval’ Bengali literature intrigued me most in my life. It was an aspiration of a simple boatman. The boatman helped Devi Annapurna ( Goddess of food) to cross the river. In reciprocation, Devi Annapurna wanted to grant him a boon and gave him the most coveted chance to choose anything he want. The boatman uttered his choice in one simple phrase,

“Aamar santan jano thake dudhe-bhate.” The literal translation of the above-mentioned line would be- “May my progeny sustain on milk and rice.”The mention of these two things ‘milk’ and ‘rice’ is very symbolic in Bengali culture. A boatman who belongs to the marginal caste and so lowest income class of a traditional society wants his lineage to live a life of solvency or sufficiency. He did not want king’s power or wealth for his children. But just a state of living which would continue in successive generations. Can we read it as a sustainable outlook towards life? What does actually compel to adopt such sustainable way of living?

Close reading of the narratives of the women would show the cultural practices that are closely related to the elements of the nature help to shape such view towards living a life. By the term culture, I want to mean not only intellectual or artistic way of interpreting the surrounding. Culture also includes a the way a community chose to connect with every element of life. The connection includes every single performance in daily life that is required to sustain human existence within a community. It does not mean community is the limit of that connection. On the contrary, the performance of each of the community members culminate a gestalt culture that acknowledges the indebtedness towards the nature that help them to sustain life.

The culture that embodies the practice of indebtedness towards other forms of existence, invariably denigrate the ideology of supremacy of human over others. This generally has created a tradition that helped the community (on the basis of collective existence) to locate the primal needs of life and planned to protect the perennial status of the elements that catered the needs. The tradition thus chose providence over improvidence.

In that case, it can be assumed that a practice of limiting the needs and understanding the interconnections as well as the intersectionalities that lie beneath the money-based market system can give us a space to engage with the term sustainability from the point of pragmatism.